Acetaminophen and Liver Disease: Safe Dosing to Avoid Hepatotoxicity

- Colin Hurd

- 29 December 2025

- 8 Comments

Acetaminophen Dosing Calculator for Liver Health

Your Inputs

Results

Enter your information to see results

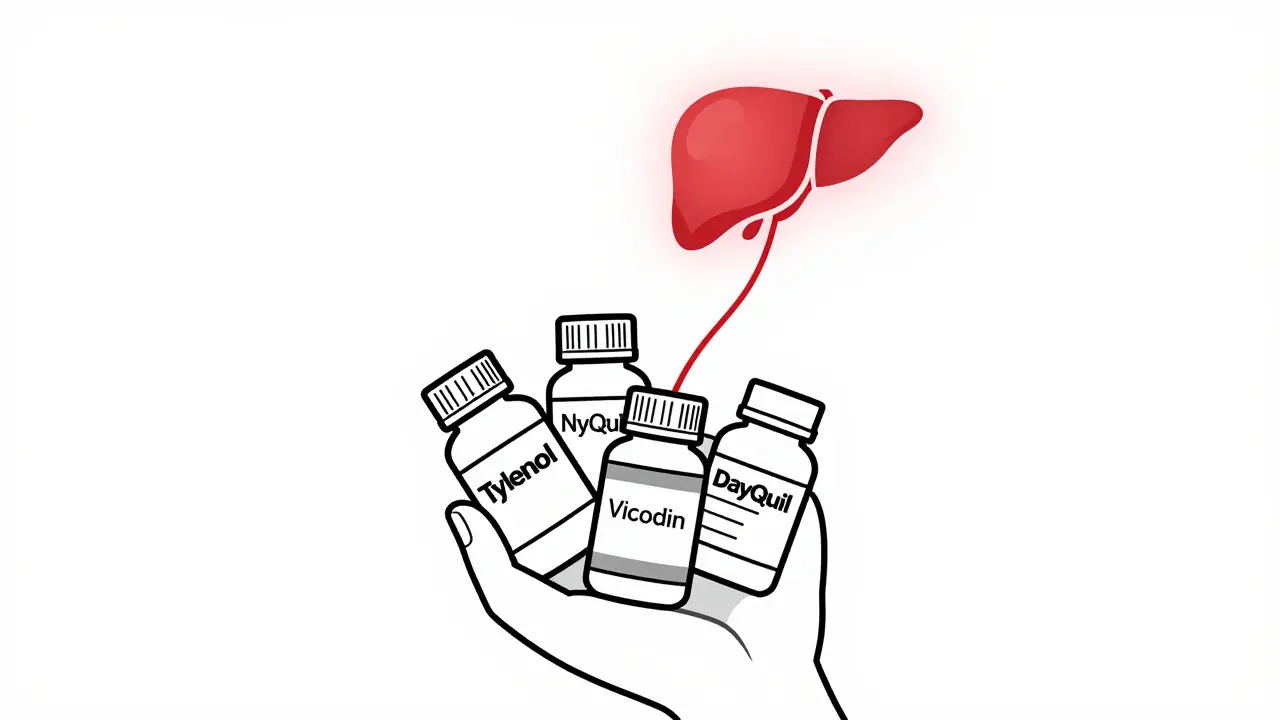

Acetaminophen is one of the most common pain relievers in the world. You’ll find it in Tylenol, NyQuil, Vicodin, Sudafed, and dozens of other over-the-counter and prescription meds. It’s effective, affordable, and widely trusted. But here’s the hard truth: acetaminophen is also the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States. Every year, about 1,600 people end up in the hospital with life-threatening liver damage because they took too much - often without even realizing it.

How Much Is Too Much?

The official maximum daily dose for adults is 4,000 milligrams (4 grams). That sounds like a lot - until you realize how easy it is to hit that limit without meaning to. Two extra-strength Tylenol pills contain 1,000 mg. Take four of them in a day, and you’ve already hit the limit. Now add a cold medicine that also has acetaminophen, and you’re over. No warning. No symptoms at first. Just silent, creeping damage.

But here’s what most people don’t know: that 4-gram limit isn’t safe for everyone. If you have liver disease - whether it’s hepatitis, fatty liver, or cirrhosis - your liver can’t handle even half that amount. Experts now recommend a max of 2,000 to 3,000 mg per day for people with existing liver conditions. Some doctors advise sticking to 2,000 mg no matter what, just to be safe.

And if you drink alcohol regularly? Even one drink a day cuts your safe limit in half. Alcohol and acetaminophen compete for the same liver enzymes. When both are present, your liver produces more of a toxic byproduct called NAPQI. Normally, your liver neutralizes NAPQI with glutathione. But if you’re drinking or your liver is already damaged, glutathione runs low - and NAPQI starts killing liver cells.

Hidden Sources of Acetaminophen

One of the biggest dangers isn’t taking too much Tylenol. It’s taking too many things that contain acetaminophen - and not knowing it.

Check the labels. Look for “APAP” on prescription bottles. That’s acetaminophen. It’s in painkillers like Percocet and Vicodin. It’s in cold and flu meds like DayQuil, TheraFlu, and Excedrin. It’s even in some sleep aids and allergy medicines. A person might take Tylenol for a headache, then take NyQuil for a cold, then take a muscle relaxant that also has acetaminophen. Three separate meds. All adding up. And no one realizes until it’s too late.

Studies show that unintentional overdose - where people just keep adding small amounts from different pills - accounts for nearly half of all acetaminophen-related liver injuries. It’s not just accidental. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable.

Why Liver Disease Changes Everything

If your liver is already struggling, it doesn’t have the backup capacity to handle extra stress. Think of your liver like a factory. When it’s healthy, it can process acetaminophen safely and still have room for other jobs - detoxing alcohol, breaking down hormones, filtering blood. But if you have cirrhosis or hepatitis, that factory is running at 70% capacity. Add acetaminophen, and the system overloads.

Research from UCI Health and the NCBI Bookshelf confirms: people with liver disease are at much higher risk of toxicity, even at doses considered “normal” for healthy people. The same 3,000 mg that’s safe for a healthy adult can cause serious harm in someone with fatty liver disease. There’s no way to test your liver’s acetaminophen tolerance. The only safe approach is to assume your limit is lower - and err on the side of caution.

Even if you’ve had liver disease in the past and your numbers have improved, your liver may still be fragile. Don’t assume you’re “cured.” The damage from past injury can linger, making you more vulnerable.

The Antidote: Acetylcysteine (NAC)

There’s good news: if acetaminophen overdose is caught early, there’s a highly effective antidote - acetylcysteine, or NAC.

NAC works by restoring glutathione levels in the liver, which helps neutralize the toxic NAPQI before it causes permanent damage. If given within 8 to 10 hours after overdose, it’s nearly 100% effective at preventing liver failure. Even if given up to 16 hours later, it still reduces the severity of damage.

Hospital treatment usually involves IV NAC: a loading dose over 15 minutes, followed by two more doses over several hours. Oral NAC is also used - it’s less effective but still helpful, especially if IV access isn’t possible.

Here’s the catch: NAC only works if you get to the hospital fast. If you take 10 pills of Tylenol and wait until you feel sick, it’s already too late. Symptoms - nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain - don’t show up until 12 to 24 hours after overdose. By then, the liver damage is underway.

That’s why doctors are trained to give NAC even before blood test results come back if someone has taken more than 10 grams or 200 mg per kilogram of body weight. Don’t wait for symptoms. If you suspect an overdose, go to the ER immediately.

What You Should Do Right Now

Here’s what actually works - not theory, not guesswork:

- Check every pill bottle. Look for “acetaminophen” or “APAP.” Write it down if you have to.

- Never combine multiple acetaminophen products. Even if one is “prescription” and another is “OTC,” they’re still the same drug.

- Stick to 3,000 mg max per day if you have liver disease. Some doctors say 2,000 mg. When in doubt, choose the lower number.

- Avoid alcohol completely while taking acetaminophen. No exceptions. Not one beer. Not one glass of wine.

- Use the smallest effective dose. You don’t need 1,000 mg for a mild headache. Try 500 mg first.

- For kids, always use the dosing syringe. Never use a kitchen spoon. A teaspoon can be 5 ml or 10 ml - and that difference can be deadly.

Also, don’t assume your pharmacist or doctor knows everything you’re taking. Many people don’t mention OTC meds unless asked. Be proactive. Bring a list of everything you take - including supplements and herbal products - to every appointment.

What Happens When the Liver Fails?

Acetaminophen toxicity doesn’t just cause pain. It shuts down your liver. That means your body can’t detoxify blood, make proteins, or regulate blood sugar. You’ll get confused. Your skin and eyes turn yellow. Your blood won’t clot. You may bleed internally. You could go into a coma. And if your liver fails, your only chance is a transplant - if you’re lucky enough to get one in time.

More than 500 people die every year from acetaminophen overdose. That’s more than all opioid overdoses combined in some years. And most of those deaths are preventable.

The problem isn’t the drug. It’s the misunderstanding. People think “natural” or “OTC” means “safe.” It doesn’t. Acetaminophen is a powerful chemical. It’s not gentle. It’s precise. And when you cross the line, there’s no second chance.

Final Reminder

If you have liver disease, acetaminophen isn’t your enemy - but it’s not your friend either. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it can hurt you if you use it wrong. Don’t guess. Don’t assume. Don’t rely on memory. Read every label. Write down your doses. Talk to your doctor. And if you ever think you’ve taken too much - go to the ER. Don’t wait. Don’t call poison control and hope for the best. Go. Now.

There’s no shame in asking for help. There’s only risk in silence.

Can I take acetaminophen if I have fatty liver disease?

Yes, but with extreme caution. Most experts recommend limiting acetaminophen to no more than 2,000 to 3,000 mg per day if you have fatty liver disease, cirrhosis, or any form of chronic liver damage. Even this amount can be risky if combined with alcohol or other liver-stressing medications. Always consult your doctor before using acetaminophen regularly - your liver may be more sensitive than you realize.

Is Tylenol safer than ibuprofen for people with liver disease?

It depends. Ibuprofen and other NSAIDs are harder on the kidneys and can raise blood pressure, but they don’t cause liver failure the way acetaminophen does. For someone with liver disease but healthy kidneys, ibuprofen might be a better short-term choice - but only at the lowest effective dose and for a few days at most. Neither is risk-free. Always discuss alternatives with your doctor.

How do I know if I’ve taken too much acetaminophen?

You often won’t know until it’s too late. The first symptoms - nausea, vomiting, sweating, and abdominal pain - usually appear 12 to 24 hours after overdose. By then, liver damage may already be underway. If you suspect you’ve taken too much - even if you feel fine - go to the ER immediately. Blood tests can measure acetaminophen levels, and treatment with NAC is most effective if started early.

Can I take acetaminophen while drinking alcohol occasionally?

No. Even one drink can significantly increase your risk of liver damage from acetaminophen. Alcohol slows down the liver’s ability to process the drug safely, leading to buildup of toxic metabolites. There is no safe level of alcohol consumption when taking acetaminophen. If you drink, avoid acetaminophen entirely. Use other pain relief options or talk to your doctor about alternatives.

What should I do if I accidentally took too much acetaminophen?

Call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room immediately. Do not wait for symptoms. Do not call poison control and wait for advice - time is critical. Bring the medication bottle with you so doctors can see exactly what you took. If you took more than 10 grams or 200 mg per kilogram of body weight, treatment with acetylcysteine (NAC) should begin right away, even before test results are back.

Are children at risk of acetaminophen toxicity too?

Yes. Children are especially vulnerable to dosing errors. The recommended dose is 10 to 15 mg per kilogram of body weight every 4 to 6 hours, with a maximum of 80 mg per kg per day. Never use a kitchen spoon - always use the syringe or measuring cup that comes with the medicine. Overdose in children can cause liver failure just like in adults. If you suspect your child took too much, go to the ER immediately.

Next Steps

If you have liver disease and use acetaminophen regularly, schedule a medication review with your doctor. Bring a list of every pill, liquid, and supplement you take - even the ones you think are harmless. Ask: “Is this safe for my liver?”

If you’re caring for someone with liver disease, help them read labels. Set up pill reminders that don’t include acetaminophen. Keep a log of daily doses.

If you’ve ever taken more than you meant to - even once - talk to your doctor. You’re not alone. And you’re not to blame. But now you know. And knowledge is the first step to staying safe.

Comments

Jasmine Yule

So I just realized I’ve been taking Tylenol for my headaches AND DayQuil for my colds like it’s nothing… and I have fatty liver. 😳 I’m deleting every OTC med with APAP from my cabinet right now. This post literally saved me from a hospital trip. Thank you.

December 30, 2025 AT 07:11

Teresa Rodriguez leon

I don’t care what anyone says-acetaminophen is a silent killer and people treat it like candy. My cousin died from this. No warning. No second chance. Don’t be her.

December 31, 2025 AT 01:47

Manan Pandya

It’s critical to note that the 4,000 mg daily limit was established based on healthy adult populations, not those with pre-existing hepatic impairment. The pharmacokinetic clearance of acetaminophen is significantly reduced in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), leading to prolonged half-life and increased NAPQI accumulation. Even 2,000 mg may exceed metabolic capacity in advanced fibrosis. Always consult hepatology guidelines-this isn’t a suggestion, it’s biochemistry.

January 1, 2026 AT 03:19

Aliza Efraimov

OMG I just checked my medicine cabinet and found FOUR different bottles with APAP in them-including my ‘all-natural’ sleep aid. I’m crying. I’ve been taking this for years thinking I was being careful. I’m going to the ER tomorrow just to get my liver enzymes checked. This is terrifying. Thank you for writing this. I feel seen.

January 3, 2026 AT 01:22

Nisha Marwaha

From a clinical hepatology perspective, the 2,000–3,000 mg ceiling for patients with liver disease is supported by pharmacodynamic modeling from the 2021 AASLD guidelines. The hepatic glutathione depletion threshold is reached at lower cumulative doses in cirrhotic patients due to reduced synthetic capacity and mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, concurrent CYP2E1 induction from chronic low-dose alcohol consumption exacerbates oxidative stress, creating a synergistic hepatotoxic cascade. NAC remains the gold standard, but prevention via label literacy is the most cost-effective intervention. Consider integrating a medication reconciliation tool into your daily routine.

January 3, 2026 AT 07:30

Paige Shipe

People are so careless with meds. I mean, really? You take Tylenol and then a cold pill and then a sleep aid? And you wonder why your liver is messed up? It’s not rocket science. Read the label. It’s written in English. Not Chinese. Not Spanish. ENGLISH. And if you can’t read it, get glasses. Or ask someone. But don’t blame the drug. Blame yourself.

January 3, 2026 AT 23:58

Tamar Dunlop

As a Canadian living with autoimmune hepatitis, I can attest that this information is not only accurate-it is life-saving. In our healthcare system, we are often not warned adequately about OTC risks. I now carry a laminated card in my wallet listing every medication I take, with APAP clearly flagged in red. I urge all patients with chronic liver conditions to do the same. Your life depends on this level of vigilance.

January 5, 2026 AT 09:27

David Chase

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART!! 😡 People can’t even read a label?! We’ve got people dying from Tylenol because they’re too lazy to check the bottle?! And now we’re giving them NAC like it’s a freebie?! This is a PUBLIC HEALTH DISASTER!! 🚨💀 I’m telling my congressman to ban APAP from OTC meds unless it’s in single-dose blister packs with a warning laser-etched into the plastic!! 🇺🇸🔥 #StopTheLiverDeaths #APAPisKillingUs

January 6, 2026 AT 06:45