Antidepressants for Teens: Understanding the Black Box Warning and What Monitoring Really Means

- Colin Hurd

- 12 December 2025

- 9 Comments

Depression Treatment Risk Calculator

Based on FDA data from 2004 and 2023 studies: Antidepressants carry a small short-term risk but untreated depression has higher long-term consequences.

When a teenager is struggling with depression, the decision to start an antidepressant isn’t just medical-it’s emotional, scary, and loaded with conflicting advice. You’ve probably heard about the black box warning-the FDA’s strongest safety alert on antidepressants for kids and teens. It says these meds might increase suicidal thoughts. But here’s what no one tells you: the warning might be doing more harm than good.

What the Black Box Warning Actually Says

In October 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put a black box warning on all antidepressants used in children and adolescents. This wasn’t a minor note. It’s the most serious alert the FDA can issue. The message? Antidepressants may double the risk of suicidal thinking or behavior in young people under 18 during the first few months of treatment. The data behind it came from 24 clinical trials involving over 4,400 kids and teens with depression or OCD. In those studies, 4% of those taking antidepressants showed signs of suicidal thoughts or behaviors-like talking about death, writing suicide notes, or making plans. That’s compared to 2% in the placebo group. No one died in those trials. But the risk was real enough for the FDA to act. The warning was expanded in 2007 to include young adults up to age 24. It applies to every class of antidepressant: SSRIs like fluoxetine and sertraline, SNRIs like venlafaxine, even atypicals like bupropion and mirtazapine. Every prescription bottle now comes with a Patient Medication Guide that spells out this risk.The Unintended Consequences

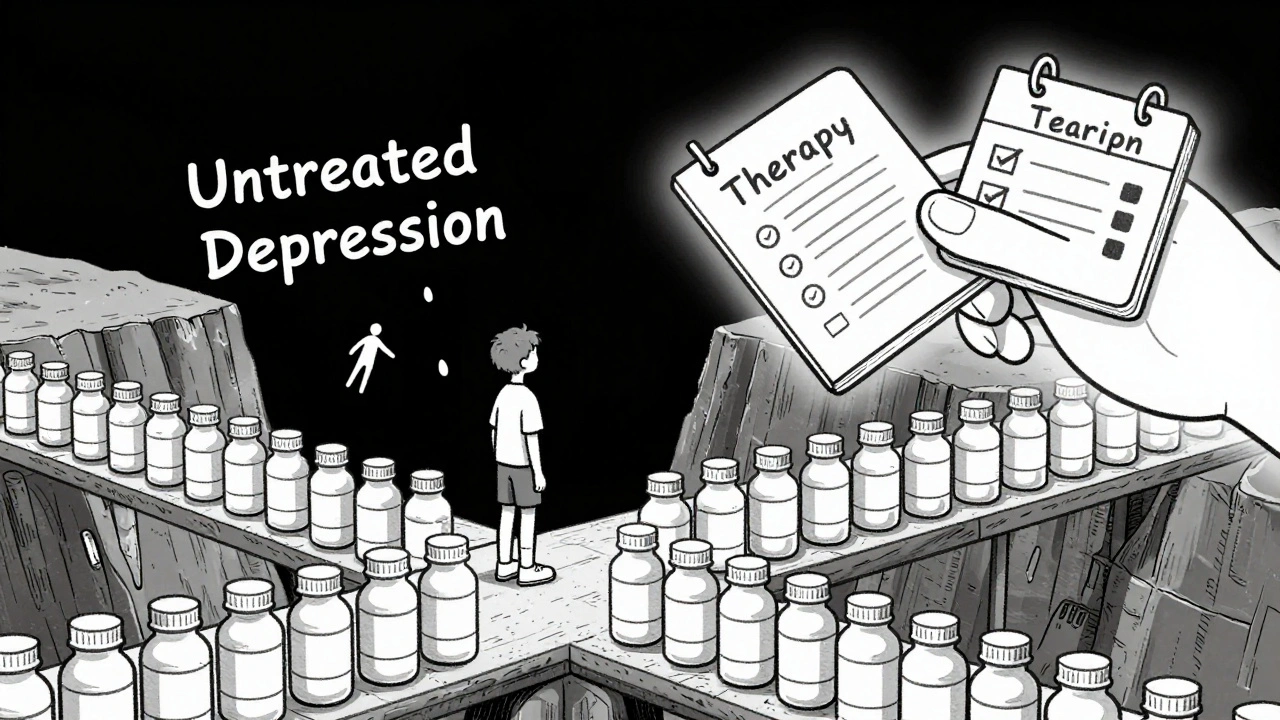

Here’s where things get complicated. After the warning went into effect, something unexpected happened: fewer teens got treated. A 2023 study in Health Affairs looked at 11 high-quality studies tracking what happened after 2004. The results were stark:- Physician visits for depression dropped by 14.5%

- Diagnoses of depression fell by 18.7%

- Antidepressant prescriptions plunged by 22.3%

- Psychotherapy visits also declined by 11.9%

Is the Risk Real-or Overstated?

The original FDA analysis was based on short-term trials, mostly 8 to 12 weeks long. These studies weren’t designed to measure long-term outcomes or real-world use. They tracked behaviors like “suicidal ideation,” which can include fleeting thoughts like “I wish I weren’t here”-not actual attempts. A 2023 Cochrane review of 34 randomized trials found the evidence on suicidality risk was “low to very low” because the number of events was so small. Many of the trials had poor reporting. Some didn’t even define what counted as “suicidal behavior.” Meanwhile, real-world data tells a different story. A 2022 survey of 1,200 adolescents on SSRIs at the Mayo Clinic found that 87% improved without any suicidal thoughts. Only 3% had transient suicidal ideas-and those went away after a dose adjustment or added therapy. Even the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) admitted in 2007 that the warning had created a “climate of fear.” Today, they’re among the groups calling for a revision. The American Psychiatric Association, the National Institute of Mental Health, and dozens of researchers agree: the benefits of antidepressants for moderate to severe depression in teens usually outweigh the risks.What Monitoring Actually Looks Like

The warning wasn’t meant to stop treatment. It was meant to make sure treatment was safe. That means close monitoring. Standard practice now includes:- Weekly check-ins for the first month-either in person or by video call

- Biweekly visits in the second month

- Monthly visits after that

What Should Parents and Teens Do?

If your teen is struggling with depression-especially if they’re withdrawn, failing school, talking about hopelessness, or losing interest in everything-they need help. Not just talk therapy. Not just waiting. Sometimes, they need medication. Here’s what to do:- Start with a full psychiatric evaluation. Depression can look like irritability in teens. It’s not always sadness.

- Ask about fluoxetine (Prozac). It’s the only antidepressant FDA-approved for teens under 18, and the most studied. It’s also the least likely to trigger agitation.

- Insist on a monitoring plan. Don’t accept a prescription without a schedule for follow-ups.

- Don’t stop meds suddenly. Withdrawal can cause mood crashes that mimic worsening depression.

- Combine meds with therapy. CBT or interpersonal therapy (IPT) works better with medication than alone.

The Bigger Picture

Teen depression rates have been rising since 2010. By 2025, nearly 1 in 5 U.S. teens report having had a major depressive episode. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for 15- to 19-year-olds. Antidepressants aren’t magic pills. But for many teens, they’re the bridge back to life. The black box warning was meant to protect. But when it stops treatment, it might be doing the opposite. The FDA’s Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee met in September 2024 to review the evidence. They’re expected to recommend changes-possibly replacing the black box with a standard warning that better reflects the risk-benefit balance. Until then, the message is simple: don’t avoid treatment out of fear. Get informed. Get monitored. And don’t let a warning label decide whether your teen lives or dies.Do antidepressants cause suicide in teens?

No, antidepressants don’t cause suicide. But in a small number of teens-about 4% in clinical trials-they may increase suicidal thoughts during the first few weeks of treatment. This is not the same as attempting suicide. Depression itself is the biggest risk factor for suicide. Untreated depression leads to far more deaths than antidepressants ever have.

Which antidepressants are safest for teens?

Fluoxetine (Prozac) is the only antidepressant FDA-approved specifically for teens under 18. It has the most evidence for safety and effectiveness in this age group. Sertraline (Zoloft) and escitalopram (Lexapro) are also commonly used and well-tolerated. Avoid paroxetine and venlafaxine in teens-they’re linked to more side effects like agitation and increased suicidality risk.

How long should a teen be monitored after starting antidepressants?

The first month is critical. Weekly check-ins are standard. The second month should include biweekly visits. After that, monthly visits are usually enough unless there are concerns. Monitoring should continue for at least three months, even if the teen feels better. Mood changes can happen slowly, and the risk of worsening symptoms peaks in the first 6 to 8 weeks.

Can therapy replace antidepressants for teens?

For mild depression, therapy alone-especially CBT or IPT-can be very effective. But for moderate to severe depression, research shows combining therapy with medication works better than either alone. If a teen is suicidal, withdrawn, or not responding to therapy after 8 to 12 weeks, medication should be considered. Delaying treatment can make depression harder to treat.

Why hasn’t the FDA changed the black box warning yet?

The FDA is cautious by design. Even though multiple studies since 2020 show the warning may have caused more harm than good, changing a label requires overwhelming evidence. The agency is waiting for more data, especially long-term outcomes. But experts agree the current warning is outdated. The Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee recommended a revision in late 2024, and a change is expected in 2025.

Comments

Webster Bull

They say the black box saves lives but it’s literally killing kids by making parents too scared to help. Depression doesn’t wait for paperwork. If your teen is silent at dinner, skipping school, staring at walls-don’t wait for perfect data. Just get them help. Now.

Stop letting fear run the clinic.

December 14, 2025 AT 10:25

Scott Butler

Typical liberal overreaction. You want to drug up kids because you’re too lazy to teach them discipline. Back in my day we got spanked for being sad. Now we hand out SSRIs like candy. This is why America’s falling apart.

December 15, 2025 AT 09:23

Ronan Lansbury

Of course the FDA won’t change it. The pharmaceutical lobby owns the FDA. They profit from fear. The black box keeps parents terrified and prescriptions flowing. Meanwhile, the real cause? Social media, screen addiction, and the collapse of community. But nobody wants to talk about that. Too inconvenient for the profit model.

They’ll change the label in 2025… right after they’ve sold another billion dollars worth of pills.

December 15, 2025 AT 09:27

sharon soila

Every child deserves a chance to feel better. Medication isn’t a crutch-it’s a tool. Just like glasses for bad eyesight. If your teen is drowning, you don’t wait for the perfect life jacket. You throw them one.

And you hold their hand while they learn to swim.

December 15, 2025 AT 17:20

nina nakamura

87% improved? That’s cherry-picked data. The 3% who had suicidal thoughts? They’re the ones who died later. You think the FDA doesn’t know this? They’re just too busy taking pharma money to care. Your ‘monitoring’ is a joke. One video call a week? Please. You’re just checking boxes while your kid slips away.

December 16, 2025 AT 12:18

Tom Zerkoff

Let’s be clear: the black box warning was never meant to prevent treatment. It was meant to ensure safety through vigilance. The real failure isn’t the label-it’s the system that let fear replace action.

Parents need education, not panic. Doctors need time, not pressure. Teens need support, not stigma.

Changing the label won’t fix that. But starting the conversation? That’s the first step.

December 16, 2025 AT 14:41

Sheldon Bird

My cousin started on Prozac last year. First two weeks she cried all the time. We were terrified. But her therapist stayed on top of it-weekly calls, open talks, no judgment.

Now she’s playing guitar again. Got a part-time job. Smiles at breakfast.

Don’t let the warning scare you. Let it guide you. 🙏

December 17, 2025 AT 11:44

Karen Mccullouch

Ugh I’m so sick of this. You people treat depression like it’s a bad hair day. My sister took meds and became a zombie. She lost her spark. You think that’s better than crying in her room? No. Therapy should be the ONLY option. Pharma wants you dependent. Wake up.

And stop blaming the warning. It’s the only thing keeping our kids safe.

😭

December 17, 2025 AT 14:44

Michael Gardner

Wait, so the warning caused more suicides, but the meds didn’t? That’s like saying seatbelts cause car crashes because people drive faster when they wear them. Correlation isn’t causation. And if you’re going to blame the FDA, why not blame the media for screaming ‘suicide drug’ for 20 years? The real villain is panic, not pills.

December 19, 2025 AT 07:28