Opioid Tolerance Explained: Why Medication Doses Increase Over Time

- Colin Hurd

- 6 February 2026

- 15 Comments

Opioid Tolerance Risk Calculator

Based on CDC and PCSS guidelines, this tool estimates overdose risk after periods of abstinence. Your tolerance decreases significantly after 2+ weeks without opioids, increasing overdose risk when restarting at previous doses.

Overdose Risk Assessment

When people develop opioid tolerancea physiological adaptation where the body reduces response to opioids over time, requiring higher doses for the same effect, it's not just about addiction-it's a measurable biological process. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)a federal agency regulating drugs and medical devices defines tolerance as "exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug's effects over time" (FDA Drug Labeling, 2008). This process affects millions of people using opioids for pain management or other reasons.

What exactly is opioid tolerance?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)a U.S. federal agency focused on public health explains that opioid tolerance specifically refers to reduced response requiring higher doses for the same effect. This differs from dependence, where the body adjusts to regular opioid use and causes withdrawal symptoms when stopped, and opioid use disorder (OUD), which involves problematic use causing significant impairment or distress.

How does your body adapt to opioids?

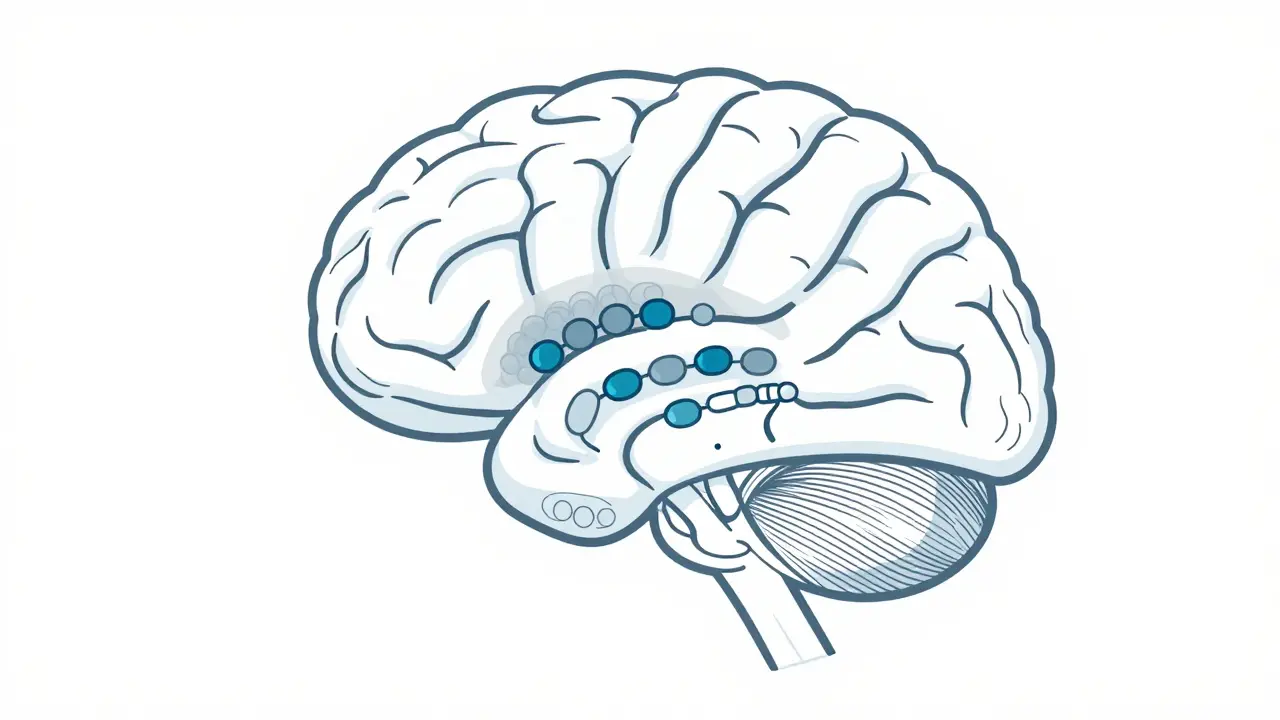

At the molecular level, opioid tolerance develops through changes in the mu-opioid receptor (MOR)the primary receptor for most opioid drugs, encoded by the OPRM1 gene. Research in Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine (2021) shows prolonged opioid exposure triggers receptor desensitization, internalization, and downregulation. Inflammatory factors like TLR4a toll-like receptor involved in immune response and NLRP3 inflammasomesprotein complexes that trigger inflammation also play a role in this process.

When opioids bind to these receptors in the brain and spinal cord, they initially cause pain relief and euphoria. But with repeated use, the nervous system adapts by reducing receptor sensitivity and altering signaling pathways. This means the same dose no longer works as well, leading to dose escalation. The British Journal of Anaesthesia (1998) notes tolerance develops at different rates for different effects-analgesic tolerance might be slower than tolerance to respiratory depression in some cases.

Tolerance vs. dependence vs. opioid use disorder

Many confuse opioid tolerance with dependence or addiction. The Providers Clinical Support System (PCSS)a national organization providing clinical support for opioid treatment clarifies this distinction. Tolerance means needing higher doses for the same effect. Dependence involves physical withdrawal symptoms when stopping opioids. OUD is a chronic disorder characterized by compulsive drug use despite harm.

For example, someone with tolerance might need more morphine for pain relief, but stopping the drug doesn't cause withdrawal. Someone dependent would experience symptoms like nausea or anxiety if they quit. OUD includes both tolerance and dependence but adds behavioral issues like failed attempts to quit or neglecting responsibilities.

Why doses increase-and why it's dangerous

As tolerance develops, patients often need higher doses to achieve pain relief. The CDC reports that approximately 30% of patients prescribed long-term opioids require dose escalation within the first year. This creates a dangerous cycle: higher doses increase overdose risk, especially when combined with other substances like alcohol or benzodiazepines.

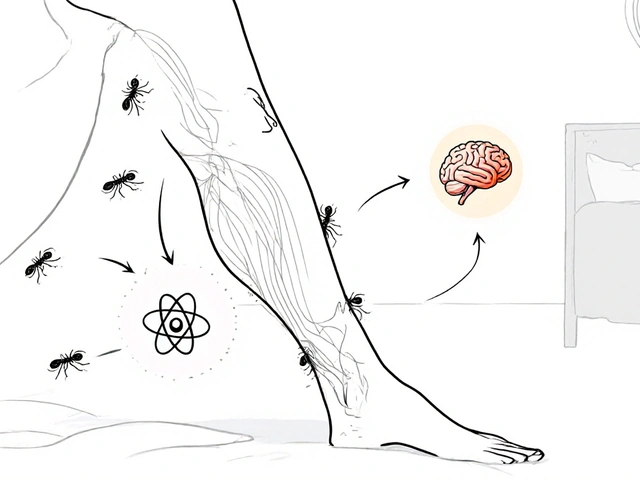

Another critical risk is tolerance loss during periods of abstinence. The PCSS notes that patients who stop opioids for weeks or months lose tolerance, making them vulnerable to overdose if they return to previous doses. Studies show 74% of fatal overdoses among people with OUD occur within weeks after release from incarceration. This explains why the CDC's current overdose prevention campaign targets recovery with the message: "Your tolerance is lower now-start with a fraction of your previous dose."

How healthcare providers manage tolerance

Clinicians use several strategies to address tolerance. Before increasing doses above 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)a standard measure for opioid potency per day, the CDC recommends reevaluating treatment goals and considering non-opioid alternatives. Doctors may also test for tolerance using blood tests combined with physical exams to assess opioid levels and signs of intoxication.

Another approach is opioid rotation-switching to a different opioid medication. Dr. B.J. Collett's work in the British Journal of Anaesthesia (1998) highlights this as a solution when dose escalation causes intolerable side effects. For instance, switching from morphine to hydromorphone might provide better pain control without increasing doses.

What you should know about tolerance loss during recovery

People in recovery often don't realize their tolerance has decreased. The PCSS states that 65% of overdose deaths among people in recovery involve returning to previous use patterns without dose adjustment. This is especially dangerous with illicit fentanyla synthetic opioid 50-100 times stronger than morphine, which varies wildly in potency-sometimes by 50-fold within the same batch.

Education is key. If you've been abstinent from opioids, even for a short time, start with a much lower dose than before. The Lake County Indiana Health Department emphasizes this is "crucial" for preventing overdose deaths during recovery. Always consult your doctor before restarting opioids after a break.

Current research fighting tolerance

Scientists are working on ways to prevent or reverse opioid tolerance. Research in Spandidos Publications (2021) shows TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors may help maintain analgesic efficacy without dose escalation. The FDA's 2023 draft guidance encourages developing new analgesics with reduced tolerance potential.

Early clinical trials combining low-dose naltrexone with opioids show promise. The PCSS reports a 40-60% reduction in required dose escalation among trial participants. These findings offer hope for safer pain management in the future.

Is opioid tolerance the same as addiction?

No. Opioid tolerance is a physiological adaptation where the body reduces response to the drug, requiring higher doses for the same effect. Addiction, or opioid use disorder (OUD), involves compulsive drug use despite harm, including behavioral issues like failed quit attempts or neglecting responsibilities. Tolerance can occur without addiction, but it often contributes to the development of OUD.

Can you reverse opioid tolerance?

Yes, but it takes time. Tolerance is reversible when opioid use stops, though the timeline varies. For example, someone who stops taking opioids for several weeks may find their tolerance decreases, making them more sensitive to the drug. However, this doesn't mean the body returns to its original state immediately-recovery depends on individual factors like genetics and duration of use. Always consult a healthcare provider before adjusting doses after a break.

Why do some people develop tolerance faster than others?

Genetics play a major role. Variations in the OPRM1 gene affect how the mu-opioid receptor functions, influencing how quickly tolerance develops. Other factors include metabolism, age, overall health, and the specific opioid used. For instance, fentanyl tends to cause faster tolerance than morphine due to its potency. Lifestyle factors like chronic stress or inflammation can also accelerate tolerance.

What happens if you stop taking opioids for a while?

Stopping opioids for even a short time can cause tolerance loss. This means your body becomes more sensitive to the drug. If you return to your previous dose after a break, you risk overdose. Studies show 74% of fatal overdoses in people with opioid use disorder happen within weeks after release from incarceration, often because they resumed previous doses without adjusting for lost tolerance. Always restart at a much lower dose under medical supervision.

How do doctors test for opioid tolerance?

Doctors assess tolerance through clinical evaluation rather than specific tests. They look at dose requirements for pain relief, side effects, and whether the medication is still effective. Blood tests may measure opioid levels in the body, but these are used alongside physical exams and symptom assessment. The key is whether the current dose provides adequate pain control without excessive side effects-this helps determine if tolerance has developed.

Are there alternatives to opioids for managing pain?

Yes. Non-opioid options include physical therapy, acupuncture, cognitive behavioral therapy, and medications like NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen), gabapentin, or antidepressants. The CDC recommends trying these before increasing opioid doses. For severe pain, doctors may use non-opioid combinations or regional nerve blocks. Always discuss alternatives with your healthcare provider to find the safest approach for your situation.

Why is fentanyl particularly dangerous with opioid tolerance?

Fentanyl is 50-100 times more potent than morphine, and street versions vary widely in strength-sometimes by 50-fold within the same batch. People with tolerance to prescription opioids may underestimate fentanyl's potency, leading to accidental overdose. The DEA warns that even small amounts can be fatal. This makes fentanyl-adulterated drugs especially risky for those with opioid tolerance, as they may not realize how little is needed to cause overdose.

Comments

Sarah B

Tolerance isn't addiction

February 8, 2026 AT 00:04

Eric Knobelspiesse

Hey so like tolerance is just the body getting used to it right But wait isn't that addiction No wait different thing Idk maybe I'm wrong but maybe the body just builds a tolerance like how you get used to coffee

February 8, 2026 AT 08:55

Heather Burrows

Oh how interesting. So tolerance is just a biological process? But what about the moral implications? I mean, shouldn't we be focusing on why people are using opioids in the first place?

February 10, 2026 AT 07:22

Ritu Singh

While it's true that tolerance is a physiological adaptation, it's important to distinguish it from addiction. The biological mechanisms involve mu-opioid receptor changes, but societal factors also play a role. We must approach this with compassion and evidence-based strategies.

February 11, 2026 AT 04:02

Mark Harris

Hey, tolerance is real but don't worry! There are ways to manage it. Talk to your doctor about alternatives. You got this!

February 12, 2026 AT 15:49

Savannah Edwards

When I first learned about opioid tolerance, I was really concerned. It's not just about addiction; it's a complex physiological process. The body adapts by changing receptors, which is fascinating but scary. I've heard stories from friends who've had to increase doses, and it's heartbreaking. The CDC data shows 30% of patients need higher doses within a year, which is alarming. But we need to remember that tolerance is different from dependence. Dependence is when your body reacts to withdrawal, but tolerance is just needing more for the same effect. It's crucial to understand this distinction to avoid stigma. For example, someone with chronic pain might develop tolerance without addiction. The key is proper medical supervision. Doctors should monitor patients closely and consider non-opioid options. Also, tolerance loss during abstinence is a huge risk for overdose. I read that 74% of fatal overdoses happen within weeks after release from prison. That's why education is so important. People in recovery need to know to start with much lower doses. It's all about safety and compassion. We need better support systems for those struggling. Let's focus on solutions, not judgment. The science is clear, but the human side matters too. We can't forget that behind every statistic is a person trying to manage their pain. It's time to approach this issue with empathy and evidence. Let's work together to make healthcare safer for everyone.

February 13, 2026 AT 16:57

Mayank Dobhal

74% of overdoses post-release? That's insane. We need to fix this now. No more excuses.

February 14, 2026 AT 19:09

Marcus Jackson

Some people think tolerance is the main issue but it's just part of the problem. The real issue is people not following medical advice. Doctors should be stricter.

February 16, 2026 AT 08:25

Natasha Bhala

Hey there, you're right it's crazy. But we can do better. Talk to your doctor, there are options. You're not alone. <3

February 18, 2026 AT 07:53

Gouris Patnaik

Doctors being stricter? What about the real problem? The system is broken. We need national solutions not just blaming individuals.

February 20, 2026 AT 06:45

Jesse Lord

Understanding tolerance is key to helping people. It's not about addiction it's about science and compassion. We need to support those struggling

February 21, 2026 AT 10:07

AMIT JINDAL

Oh my goodness this is spot on! But let's take it a step further. The real solution lies in global cooperation and innovative science. For instance, TLR4 inhibitors could revolutionize pain management 🌍✨. We must invest in research to save lives. This isn't just a US problem it's a human issue. Let's all work together! 😊

February 22, 2026 AT 11:02

Catherine Wybourne

Yes, global cooperation! Because nothing says 'solution' like another international committee. 🙄 But seriously, TLR4 inhibitors sound promising. Let's hope they actually work and don't just get buried in bureaucracy.

February 24, 2026 AT 05:59

Ashley Hutchins

People shouldn't be taking opioids at all. It's all their fault for getting addicted. The government is too soft on this. We need stricter laws

February 25, 2026 AT 06:22

Lakisha Sarbah

I understand your concern but it's not that simple. Many people use opioids for legitimate pain. Blaming them isn't helpful. We need better education and support systems

February 26, 2026 AT 06:48