Patent Law and Generics: How Patents Protect Innovation in Pharmaceutical Drugs

- Colin Hurd

- 20 November 2025

- 8 Comments

When a drug company spends over $2.6 billion and more than a decade to bring a new medicine to market, it needs protection. That’s where patent law comes in. Without it, any company could copy the drug the moment it’s approved, leaving the original developer with no way to recover its investment. But patent law doesn’t just protect big pharma-it also creates a path for cheaper generic drugs to enter the market. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s designed to balance two competing goals: encouraging innovation and ensuring access to affordable medicine.

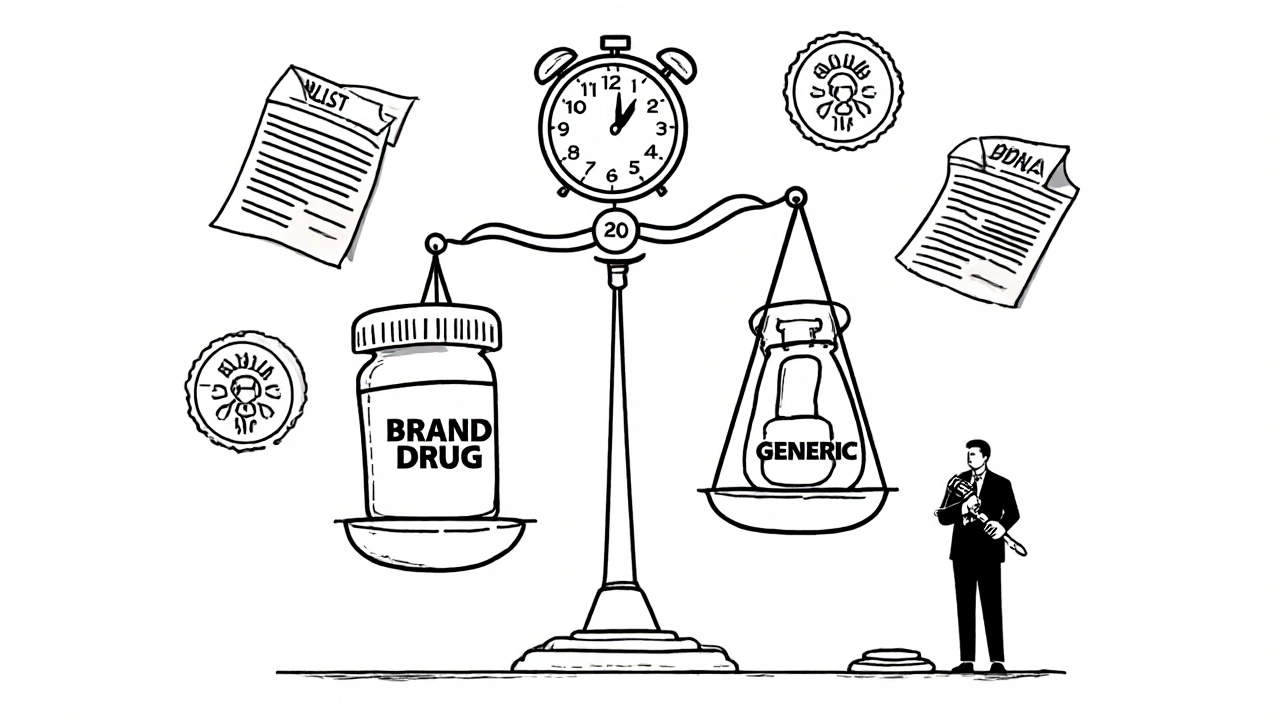

How Patents Work in Drug Development

A pharmaceutical patent gives a company the exclusive right to make, sell, and distribute a new drug for 20 years from the date the patent is filed. But here’s the catch: most of that 20-year clock ticks away during clinical trials and FDA review. By the time a drug hits shelves, it might only have 10 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity left. That’s not enough time to recoup the billions spent on research, especially when the success rate for new drugs is less than 10%.

That’s why the U.S. created the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984-better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. It was a compromise. Brand-name companies got extra time to make up for delays in FDA approval. Generic manufacturers got a clear legal pathway to enter the market after patents expired. The law didn’t eliminate patents-it restructured how they interact with drug approval.

The Orange Book and the Patent Linkage System

Every approved drug in the U.S. is listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. This isn’t just a directory-it’s a legal map. Brand companies must list every patent they believe covers their drug: the active ingredient, how it’s made, how it’s taken, even special coatings or delivery systems. Generic makers check this list before they start developing their version.

If a generic company finds a patent they think is invalid or doesn’t apply, they can file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification. This is a legal challenge. It says: “We’re going to make this drug, and we believe your patent doesn’t hold up.” Once filed, the brand company has 45 days to sue for infringement. If they do, the FDA is automatically blocked from approving the generic for 30 months. That’s a big deal. Even if the patent is weak, the brand gets years of extra protection just by filing a lawsuit.

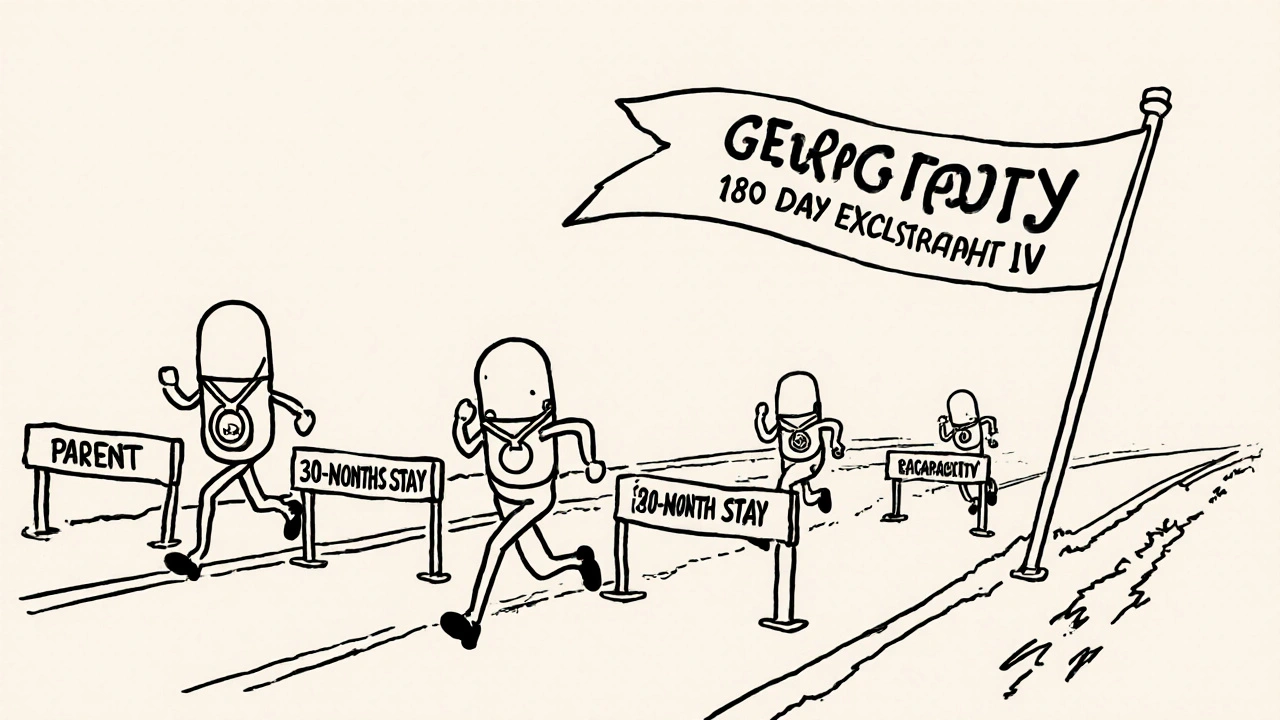

Why the First Generic Gets a Big Advantage

The Hatch-Waxman Act doesn’t just let generics in-it rewards the first one to challenge a patent. The first generic to file a successful Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generics can enter during that time. That’s a goldmine.

Why? Because state laws require pharmacists to substitute generics when they’re available. So when the first generic hits, pharmacies start filling prescriptions with it instead of the brand. The price drops fast-sometimes by 70% in six months. The first generic maker can charge a little more than others, but still way less than the brand. In some cases, that 180-day window earns hundreds of millions in revenue.

That’s why companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz spend millions on legal teams just to be first in line. They’re not just making drugs-they’re playing a high-stakes game of patent chess.

What Happens When Patents Expire

When a drug’s patent runs out, the market flips. Take Prozac. When Eli Lilly lost its patent in 2001, generic versions flooded in. Within a year, Prozac’s U.S. sales dropped by 70%. The company lost $2.4 billion in annual revenue. But patients paid less. Pharmacists switched prescriptions. Insurance companies saved money. The system worked as intended.

Today, 91% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. Yet they cost only 24% of what brand drugs do. In 2022, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion. That’s not a small number-it’s the equivalent of covering Medicare Part D for over 10 million people.

Generic versions of common drugs like ibuprofen or metformin now cost pennies. Boots’ Brufen brand once sold for $10 a bottle. Today, generic ibuprofen sells for $1.50. The medicine is identical. The only difference? The label.

The Dark Side: Evergreening and Patent Thickets

But not all patent use is fair. Some companies stretch their exclusivity by filing dozens of secondary patents-on tiny changes that don’t improve the drug. This is called evergreening. For example, Humira, a top-selling biologic for arthritis, had over 240 patents filed across 70 families. That’s not innovation-it’s legal padding. These patents delayed biosimilar competition in the U.S. until 2023, even though Europe had generics since 2018.

Another tactic is “product hopping.” A brand company slightly reformulates a drug-say, changing from a pill to a tablet-and pushes doctors to switch patients. Then they let the old version’s patent expire while keeping the new one protected. Patients end up paying more for a drug that’s barely different.

The 2022 CREATES Act tried to stop this by forcing brand companies to supply samples to generic makers. Before, some brands refused to give samples, claiming safety concerns, which blocked generics from testing equivalence. Now, they can be sued if they withhold samples without good reason.

Pay-for-Delay: When Generics Get Paid to Wait

Here’s the weirdest part: sometimes, brand companies pay generics not to enter the market. These are called “pay-for-delay” deals. The brand pays the generic maker millions to delay launching its cheaper version. The FTC says these deals cost consumers $3.5 billion a year.

It’s a quiet collusion. The generic gets a big payout. The brand keeps its monopoly. Patients pay more. Courts have ruled these deals illegal in some cases, but they still happen. That’s why Congress keeps trying to pass the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act-to ban them outright.

Biologics and the New Frontier

Biologics-drugs made from living cells, like insulin or cancer treatments-are harder to copy than pills. That’s why the 2010 Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act created a separate pathway for biosimilars. But it didn’t work as planned.

In 2017, a court case called Amgen v. Sandoz threw a wrench into the system. The court ruled that the “patent dance”-a step-by-step process for sharing patent info between brand and biosimilar makers-was optional. That opened the door to more lawsuits and delays. Today, biosimilar entry is still slow. Humira’s first biosimilar didn’t arrive in the U.S. until 2023, more than 20 years after its launch.

Is the System Broken?

PhRMA, the drug industry’s main lobbying group, says patents are essential. Without them, no one would spend $83 billion a year on R&D. They’re right. New cancer drugs, rare disease treatments, and mRNA vaccines wouldn’t exist without the promise of exclusivity.

But the Association for Accessible Medicines counters: generics prevented $2.2 trillion in healthcare costs from 2010 to 2020. That’s more than the entire U.S. defense budget over that time.

The truth is, the system works-but only if it’s enforced fairly. When patents are used to delay competition, not to reward innovation, the public pays. When generics enter quickly, patients win.

The 30-month stay, the 180-day exclusivity, the Orange Book-all of it is still in place. Over 97% of new generic applications still use the Paragraph IV process. But the game is getting harder. Litigation takes longer. The average time from patent expiry to generic entry jumped from 2.1 years in 2005 to 3.6 years in 2020.

What’s Next?

The future of patent law and generics depends on three things: transparency, enforcement, and reform.

First, the Orange Book needs cleanup. Listing every minor patent doesn’t protect innovation-it hides it. The FDA should require only patents that directly cover the drug’s active ingredient or approved use.

Second, pay-for-delay deals need teeth behind the ban. Right now, fines are weak. The FTC needs more power to stop them before they happen.

Third, biosimilars need a clearer path. The patent dance should be mandatory. And the 30-month stay shouldn’t apply to biologics-it’s too long for complex drugs.

Patents aren’t the enemy. They’re the engine of innovation. But when they’re used as a tool to block competition instead of reward risk, the system fails. The goal isn’t to eliminate patents-it’s to make sure they serve patients, not just profits.

How long does a pharmaceutical patent last?

A pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But because drug development takes 10-12 years on average, most drugs only have 8-12 years of actual market exclusivity after FDA approval. The Hatch-Waxman Act allows patent term restoration to make up for delays during FDA review, adding up to 5 extra years in some cases.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 is a U.S. law that balances drug innovation and generic access. It lets generic manufacturers challenge brand patents before launch and grants brand companies extra patent time to make up for FDA delays. It also gives the first generic challenger 180 days of exclusive marketing rights, creating a financial incentive to take legal risks.

Why do generic drugs cost so much less?

Generic drugs cost 80-85% less because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. They prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand drug-meaning they work the same way in the body. The cost savings come from skipping R&D, marketing, and promotion. Generic makers only pay for manufacturing and FDA approval.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal notice filed by a generic drug maker when it believes a brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand company to sue. If they do, FDA approval of the generic is automatically delayed for up to 30 months, regardless of whether the patent is actually valid.

Can a generic drug enter the market before a patent expires?

Yes, but only if the generic company files a Paragraph IV certification and successfully challenges the patent in court. If they win, the FDA can approve the drug before the patent expires. Many generics enter early this way-especially when patents are weak or overly broad.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs made from chemicals. Biosimilars are similar but not identical copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells. Because biologics are harder to replicate, biosimilars require more testing and face longer approval times. They also don’t benefit from the same 180-day exclusivity as generics.

How do patents affect drug prices in the U.S. vs. other countries?

The U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices, so brands can charge what they want during patent protection. In countries like Canada, the UK, or Germany, governments negotiate prices and often force early generic entry. That’s why the same drug can cost 5-10 times more in the U.S. than elsewhere. Once patents expire, prices drop everywhere-but the U.S. takes longer to get there.

Comments

Logan Romine

So let me get this straight - we spend billions to invent a drug, then let some guy in a basement in Bangladesh copy it for $1.50? 🤡💊

Meanwhile, my insulin costs $300 a vial because ‘patents.’

Patents aren’t innovation - they’re rent-seeking with a lab coat. 🧪💸

November 20, 2025 AT 23:40

Leo Tamisch

The entire pharmaceutical patent regime is a grotesque parody of capitalism. It’s not meritocracy - it’s legal monopolism disguised as incentive. The 20-year term is archaic in the age of AI-driven drug discovery. We’re not protecting innovation; we’re protecting shareholder dividends from the moral consequences of pricing life-saving medicine beyond human reach. The Orange Book? More like the Orange List of Corporate Greed™. 🏛️💸

November 21, 2025 AT 11:59

Franck Emma

I lost my dad because they wouldn’t lower the price of his cancer drug. Now I watch these guys talk about ‘balance’ like it’s a TED Talk. 💔

November 22, 2025 AT 02:14

Eliza Oakes

Wait, so the first generic gets 180 days of exclusivity? That’s not competition - that’s a cartel with a badge. And don’t even get me started on ‘pay-for-delay.’ You mean Big Pharma pays the competition to NOT show up? That’s not capitalism. That’s mafia economics with a FDA stamp. 🤭

November 23, 2025 AT 12:19

Simone Wood

Honestly tho, the Orange Book is a total mess. Like, why are they listing patents for the *color* of the pill? That’s not protecting innovation, that’s just trolling the generics. And the 30-month stay? Bro, that’s just a delay tactic. I’ve seen cases where the patent was obviously junk and they still got 2 extra years. It’s systemic corruption. 🤷♀️

November 23, 2025 AT 12:25

Swati Jain

Look, I get it - R&D is expensive. But when you have a drug that saves lives and you’re charging $50,000 a year for it? That’s not capitalism. That’s a moral failure. The system isn’t broken - it’s designed this way. The 180-day exclusivity for generics? That’s the only real win. But even that’s being gamed. We need transparency, not more loopholes. Let’s fix the game, not just the players. 💪🌍

November 24, 2025 AT 11:59

Florian Moser

This is actually one of the most balanced takes I’ve seen on pharma patents. The Hatch-Waxman Act was genius for its time - it created a real middle ground. Yes, there’s abuse - evergreening, pay-for-delay, product hopping - but the core system still delivers: 91% of prescriptions are generics, and they saved $373B last year alone. The fix isn’t to tear it down - it’s to clean up the Orange Book, ban pay-for-delay, and make the patent dance mandatory for biosimilars. We can do better without breaking what works. 🙌

November 24, 2025 AT 22:50

Julia Strothers

The U.S. is the only country that lets drug companies price-gouge like this. Why? Because we’re too weak to stand up to Big Pharma. Meanwhile, Europe and Canada get the same drugs for 1/5 the price. And now you want to defend this? This isn’t innovation - it’s American imperialism disguised as free market. If you’re not outraged, you’re part of the problem. 🇺🇸💊💀

November 25, 2025 AT 00:16