Spinal Stenosis and Neurogenic Claudication: How to Recognize Symptoms and Choose the Right Treatment

- Colin Hurd

- 30 January 2026

- 14 Comments

When Walking Becomes Painful: The Real Story Behind Neurogenic Claudication

If you’ve ever felt your legs turn heavy after walking just a few blocks-like they’re filled with wet sand-and you had to stop, lean forward, or grab a shopping cart to catch your breath, you’re not alone. This isn’t just aging. It’s neurogenic claudication, the most common symptom of lumbar spinal stenosis. And it’s often mistaken for a circulation problem. The truth? Your nerves are being squeezed, not your blood flow.

Unlike vascular claudication, where pain fades with rest no matter your posture, neurogenic claudication only improves when you bend forward. That’s the key. Sit down. Lean on a cane. Push a cart. Suddenly, the burning, numbness, or weakness in your legs eases. That’s your body’s natural signal: my spine is compressed, and I need to flex to make room.

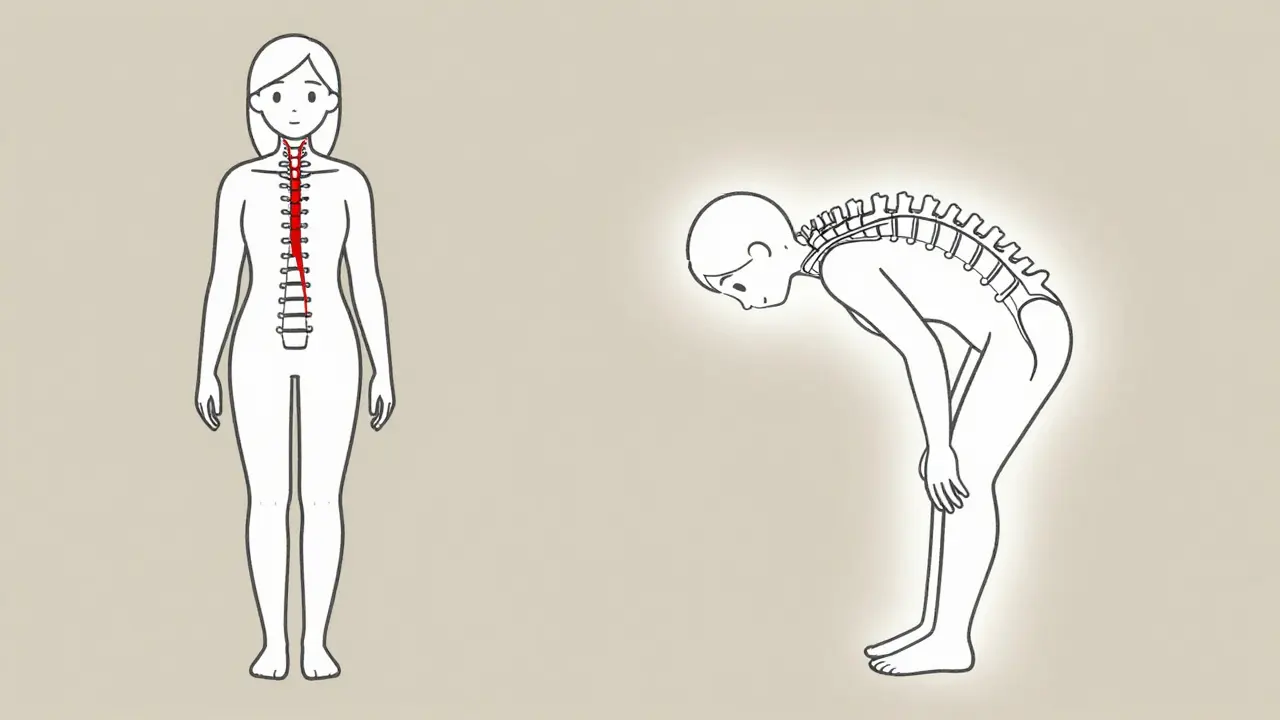

Why Bending Forward Feels Like Magic

Your spinal canal is like a narrow tunnel running through your lower back. As you age, discs flatten, ligaments thicken, and bones shift. This slowly narrows the space around your nerves. When you stand or walk, gravity pulls your spine into extension-tightening the tunnel even more. Nerves get pinched. Blood flow to them drops. That’s when pain, tingling, or weakness hits your buttocks, thighs, or calves.

But when you bend forward-like leaning over a grocery cart or sitting in a chair-you open up that tunnel. The space around your nerves expands. Pressure drops. Blood flows again. It’s not a cure, but it’s relief. That’s why doctors call it the shopping cart sign. Studies show 68% to 85% of people with confirmed spinal stenosis use this trick daily. One patient on Reddit said: “I can only walk 200 feet before my legs feel like lead. But push a cart? I’ll walk the whole store.”

How Doctors Tell It Apart From Poor Circulation

Many people are misdiagnosed with peripheral artery disease because both conditions cause leg pain with walking. But here’s how they’re different:

- Neurogenic claudication: Pain improves with bending forward or sitting. Pulse in your feet is normal. You may feel numbness or tingling. Straight leg raise test is usually negative.

- Vascular claudication: Pain fades with rest, no matter your posture. Legs feel cold. Pulses are weak or absent. Skin may look pale or shiny.

Doctors check your foot pulses first. If they’re strong, it’s likely not a blood vessel issue. They’ll ask: “Do you feel better when you sit or lean forward?” If you say yes, that’s a major clue. They might also have you do the five-repetition sit-to-stand test. If you can do it in under 10 seconds, your mobility isn’t severely affected yet.

Another sign? Wasting in the small muscles under your foot-the extensor digitorum brevis. It’s a subtle sign, but experienced spine specialists know to look for it. It’s one of the most reliable bedside markers for nerve compression.

Imaging Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

You might think an MRI will confirm everything. But here’s the catch: up to 67% of people over 60 have signs of spinal stenosis on MRI-even if they have zero pain. That means imaging alone can’t diagnose you. A narrow canal doesn’t always mean symptoms. And some people with severe pain have only mild narrowing.

That’s why diagnosis relies on your story-not just the scan. A good doctor combines your symptoms, physical exam, and imaging. If you have leg pain when walking, relief with bending forward, normal pulses, and weakness or numbness in your legs, that’s the picture. The MRI just helps rule out other causes like tumors or fractures.

First Steps: What Works Before Surgery

Most people don’t need surgery right away. In fact, 82% of early-stage patients see meaningful improvement with conservative care. Here’s what actually helps:

- Exercise: Focus on flexion-based movements-pelvic tilts, knee-to-chest stretches, and walking while leaning forward. Avoid back extensions like supermans or backward bends.

- Physical therapy: A good PT will teach you posture strategies and core stabilization. Most patients need 6 to 8 weeks of consistent therapy before seeing real change.

- Pain relief: Over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen can help with inflammation. Some doctors prescribe gabapentin or pregabalin for nerve-related burning or tingling.

- Activity modification: Use a walker or shopping cart. Ride a recumbent bike instead of walking. Sit instead of standing when possible.

One study found patients who understood the importance of forward flexion improved their walking distance by 40% in just 3 months-just by changing how they moved. No drugs. No surgery. Just smarter movement.

When Injections Might Help

If pain sticks around after 3 to 6 months of exercise and therapy, epidural steroid injections are the next step. These shots deliver anti-inflammatory medicine directly near the compressed nerves. Success rates? About 50% to 70% get temporary relief-usually lasting 3 to 6 months. It’s not permanent, but it can buy time. Some patients use it to get through a flare-up or delay surgery while building strength.

But here’s the catch: if you’ve had two or three injections with no lasting benefit, it’s time to rethink your plan. Repeated injections don’t fix the root problem-they just mask it.

Surgery: When It’s Time to Consider It

For those with ongoing weakness, numbness, or pain that stops you from living-surgery is often the best option. The goal isn’t to make you 20 again. It’s to restore your ability to walk without pain.

Common procedures:

- Laminectomy: Removes part of the bone covering the spinal canal. Most effective for central stenosis.

- Laminotomy: Removes only a small portion of bone. Less invasive, good for lateral stenosis.

- Minimally invasive decompression: Uses small incisions and specialized tools. Recovery is faster. The Superion device, FDA-approved in 2023, is one option that acts like a spacer between spinal bones-keeping the canal open without removing bone.

Studies show 70% to 80% of well-selected patients report significant improvement after surgery. One 12-month follow-up found 65% rated their outcome as “good to excellent.” But results depend on how long you waited. If you’ve had weakness for over a year, recovery is slower. Nerves don’t bounce back as easily.

What Patients Wish They’d Known Sooner

Many people spend months-or even years-going from doctor to doctor, getting misdiagnosed. One patient wrote on Healthgrades: “It took three doctors before someone asked if bending forward helped. My pulses were fine. No one looked at my posture.”

Another common regret? Waiting too long to start physical therapy. “I thought I’d just tough it out. By the time I saw a specialist, I could barely walk to the mailbox.”

But those who learn early and adapt? They thrive. One patient in Perth started using a rollator walker with a seat. She now walks her dog daily. Another switched to cycling on a recumbent bike. He’s back gardening. They didn’t need surgery. They just changed how they moved.

The Big Picture: Why This Matters More Than Ever

Spinal stenosis isn’t rare. It’s becoming more common as the population ages. In the U.S., about 200,000 adults are diagnosed each year. By 2050, the number of people over 65 will double globally. That means more cases of neurogenic claudication.

Thankfully, treatment is improving. Minimally invasive techniques are up 35% since 2018. New diagnostic tools are coming. A standardized algorithm from the International Spine Study Group is expected in late 2024, which should help doctors diagnose faster and more accurately.

Costs vary. Conservative care runs $500 to $2,000 a year. Surgery? $15,000 to $50,000. But the real cost is lost independence. The goal isn’t just pain relief-it’s getting your life back.

What to Do Next

If you’re experiencing leg pain when walking, ask yourself:

- Does the pain get worse when I stand or walk?

- Does bending forward, sitting, or leaning on something make it better?

- Do I have numbness, tingling, or weakness in my legs?

- Are my foot pulses strong and equal on both sides?

If you answered yes to most of these, see a spine specialist-not just a general practitioner. Bring your symptoms, not your MRI. Be ready to describe how you move, what helps, and what doesn’t.

Start with movement. Don’t wait. Exercise, posture, and pacing are your first line of defense. Surgery isn’t failure-it’s a tool. And it works best when used at the right time.

Is neurogenic claudication the same as sciatica?

No. Sciatica is pain caused by a pinched nerve root, often from a herniated disc. It usually affects one leg and feels sharp or electric. Neurogenic claudication is caused by narrowing of the spinal canal and affects both legs. It’s a dull, heavy pain that comes on gradually with walking and improves with forward bending.

Can I still walk if I have neurogenic claudication?

Yes-but you need to adapt. Walking is still important. Use a walker or shopping cart to lean forward. Break walks into short segments. Try a recumbent bike. The goal isn’t to stop walking-it’s to walk smarter. Many people increase their distance over time by pacing and using posture techniques.

Will I need surgery eventually?

Not necessarily. Most people manage well with conservative care. Surgery is considered only if pain or weakness persists after 3-6 months of physical therapy, exercise, and possibly injections. If you’re still able to walk, even with help, surgery isn’t urgent. But if you’re losing strength or balance, don’t delay.

What’s the difference between central and lateral spinal stenosis?

Central stenosis narrows the main spinal canal, pressing on the nerve bundle (cauda equina). This causes bilateral leg pain, heaviness, and sometimes bladder issues. Lateral stenosis narrows the side passages where individual nerve roots exit. It often causes one-sided pain, tingling, or weakness. Both can cause neurogenic claudication, but the symptoms and surgical approach differ.

Can I prevent spinal stenosis?

You can’t stop aging, but you can slow its impact. Keep your core strong. Maintain a healthy weight. Avoid prolonged sitting or standing in extension. Walk with good posture. Stay active. These habits reduce pressure on your spine and may delay the onset or severity of stenosis.

How long does recovery take after spinal surgery?

Recovery depends on the procedure. Minimally invasive decompression often allows patients to walk the same day. Most return to light activities in 2-4 weeks. Full recovery, including rebuilding strength and endurance, takes 3-6 months. Physical therapy is essential. Don’t rush. Nerves heal slowly.

Final Thought: It’s Not Just About Pain

Neurogenic claudication isn’t a death sentence. It’s a signal. A sign that your spine needs support-not punishment. The people who do best aren’t the ones who get surgery first. They’re the ones who learn their body’s language. They know when to bend. When to rest. When to push. And when to ask for help.

Comments

Diana Dougan

So let me get this straight - if I lean on a shopping cart, my legs stop feeling like concrete? Genius. Next you'll tell me yoga pants are a medical device. 🙄

February 1, 2026 AT 09:20

Rohit Kumar

This is not merely a medical condition. It is a metaphor for modern life - we are all compressed by systems that demand upright posture, yet relief only comes when we bend - literally and spiritually. The shopping cart is the new prayer wheel.

February 2, 2026 AT 21:23

Lily Steele

I started using a walker with a seat last year after my PT said 'stop trying to be a hero' and honestly? I walk farther now than I did at 50. No surgery. Just smart moves. You got this.

February 4, 2026 AT 20:19

Jodi Olson

The fact that 67 percent of people over 60 show stenosis on MRI without symptoms suggests we are medicalizing aging itself. The body is not broken. It is adapting. We must stop treating time as pathology.

February 6, 2026 AT 16:36

Beth Beltway

Of course you didn’t mention opioids. Because why fix the problem when you can just numb the pain and pretend it’s not getting worse? This whole post is a placebo dressed in clinical language.

February 7, 2026 AT 07:51

Marc Bains

I’ve seen this in my community - older folks told they just need to walk more, but no one shows them how to walk without breaking. The shopping cart sign? That’s not a quirk. That’s a cry for help. We need better access to PT, not just pamphlets.

February 7, 2026 AT 12:43

Kelly Weinhold

I used to think I was just getting old and out of shape. Then I started leaning on the grocery cart like a pro and realized - oh. My body was trying to tell me something. Now I ride my recumbent bike every morning and I swear I feel like I’ve been given back 10 years. It’s not magic. It’s mechanics. And you can do it too. Start small. Just one block.

February 9, 2026 AT 01:41

Kimberly Reker

The key detail everyone misses: neurogenic claudication doesn't hurt when you're sitting. That’s the diagnostic clue. Not the MRI. Not the pulse check. It’s the posture. If you're standing and it hurts, sit. If you're sitting and it hurts, stand. Your spine is talking. Listen.

February 9, 2026 AT 11:55

Eliana Botelho

Wait so you're telling me I don't need surgery if I just pretend I'm pushing a cart? That's it? No laser? No fusion? No 30k bill? I'm calling my doctor right now to ask if I can get a discount on a Walmart cart. Also, why does everyone here sound like a wellness influencer? This isn't a TED Talk.

February 10, 2026 AT 19:51

calanha nevin

It is critical to emphasize that while conservative management is effective for the majority, delaying surgical evaluation in the presence of progressive motor deficit or bowel/bladder dysfunction constitutes a clinical error. The data is unequivocal: early intervention in select cases yields superior functional outcomes. This post, while informative, risks minimizing the urgency of neurological deterioration.

February 12, 2026 AT 02:47

Lisa McCluskey

I had two epidurals. Didn’t help. Then I started doing pelvic tilts every morning while brushing my teeth. Three months later, I walked to the park without stopping. No one told me that tiny movements mattered. They do.

February 13, 2026 AT 16:04

owori patrick

In Nigeria, many elderly walk with sticks because they have no chairs. They lean forward naturally. No one calls it the shopping cart sign. They just live. Maybe the problem isn’t the spine - it’s the chairs.

February 13, 2026 AT 20:41

Claire Wiltshire

Thank you for highlighting the importance of patient narrative over imaging. Too often, clinicians fixate on structural abnormalities without correlating them to functional impairment. This approach - grounded in clinical reasoning and lived experience - is exactly what evidence-based care should look like.

February 15, 2026 AT 04:22

Russ Kelemen

I used to think the shopping cart trick was just a funny quirk until my dad, who’s 76, started using one after his diagnosis. He didn’t get surgery. He didn’t take pills. He just learned to move differently. Now he walks the neighborhood every morning. He says the cart isn’t a crutch - it’s his co-pilot. I wish I’d understood this sooner.

February 16, 2026 AT 07:05