Serotonin Syndrome Risk: What You Need to Know

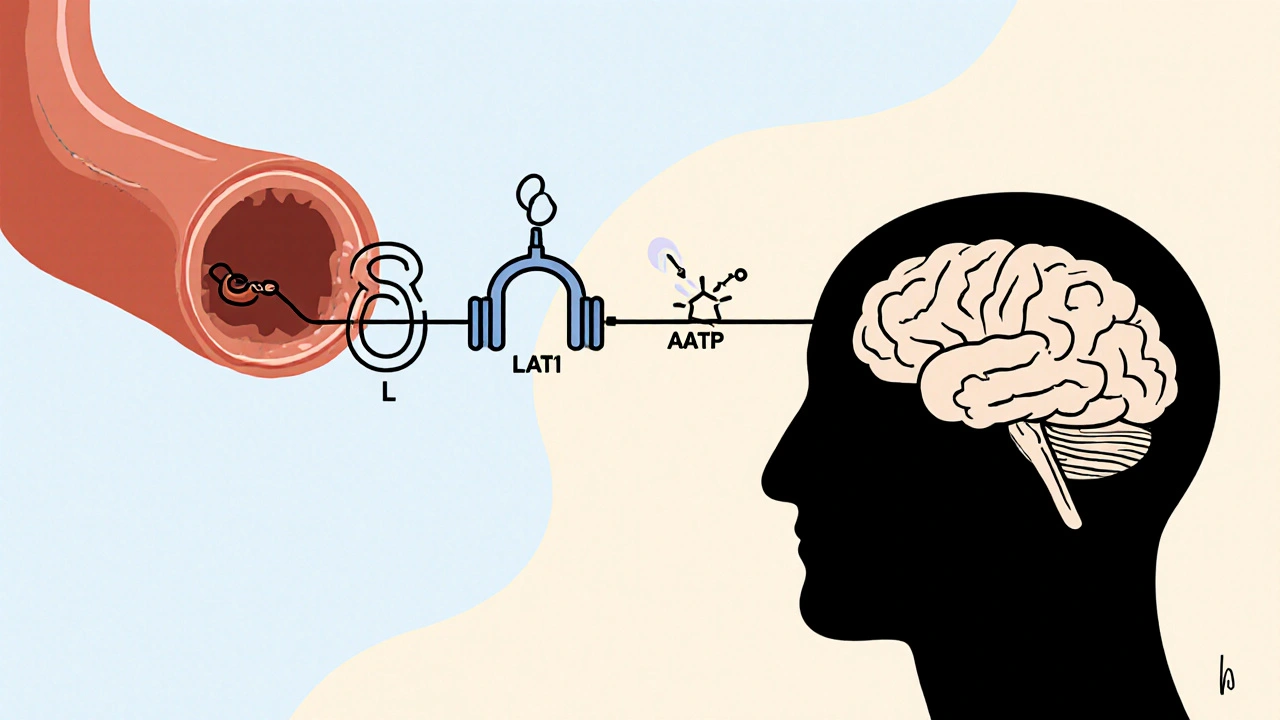

When you hear the phrase serotonin syndrome risk, the chance of a dangerous serotonin overload from certain drug combinations or overdoses, you probably think of a rare medical emergency. In plain terms, it’s the probability that your body’s serotonin system goes into overdrive, often because multiple serotonergic medicines are taken together. Serotonin syndrome, a rapid‑onset condition marked by agitation, high fever, and muscle clonus is the outcome you want to avoid. One of the most common culprits are Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antidepressants that increase serotonin levels in the brain. Understanding how these pieces fit together helps you spot danger before it spikes.

Serotonin syndrome risk climbs when drugs that raise serotonin meet another drug that either blocks its breakdown or adds more serotonin to the mix. Classic examples include monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), which stop the enzyme that normally degrades serotonin. When an SSRI meets an MAOI, the serotonin pool can skyrocket. Other prescription meds like tramadol, linezolid, or certain migraine treatments also sit in the same high‑risk group. Even over‑the‑counter supplements such as St. John’s wort can tip the balance if you’re already on a serotonergic drug. The key point: the risk isn’t just about one drug, it’s about the interaction web you create.

Key Factors Behind Serotonin Syndrome Risk

The first red flag is the presence of multiple serotonergic agents. A patient on an SSRI who starts a new painkiller (tramadol) or an antimigraine drug (triptan) instantly adds another serotonin source. Age matters too—older adults often take several prescriptions, making drug‑drug interactions more likely. Genetics play a role; some people metabolize serotonin‑affecting drugs slower, increasing their internal levels. Lastly, dosing errors, whether intentional or accidental, boost the chance of crossing the toxicity threshold. All these elements—drug class, age, genetics, dosage—form a web that raises serotonin syndrome risk, the likelihood of experiencing excess serotonin symptoms in a predictable way.

Spotting the syndrome early can be life‑saving. Typical symptoms cluster into three groups: mental changes (agitation, confusion, hallucinations), autonomic disturbances (sweating, rapid heart rate, high temperature), and neuromuscular signs (tremor, hyperreflexia, clonus). The classic “hyperreflexia and clonus” pattern is a quick bedside clue. If you notice sudden shaking, a fever over 38 °C, and a restless, uneasy feeling after starting a new drug, think serotonin toxicity. The Hunter criteria, a diagnostic tool used worldwide, helps clinicians confirm the diagnosis by matching specific symptom patterns with known drug exposure.

Treatment focuses on stopping the serotonergic agents and supporting the body while the excess serotonin clears. In mild cases, simply discontinuing the offending drugs and providing hydration may suffice. Moderate to severe cases often require hospital care: cooling measures for hyperthermia, benzodiazepines to calm agitation and reduce muscle activity, and, if needed, serotonin antagonists like cyproheptadine. The goal is to bring serotonin levels back to a safe range and prevent complications such as seizures or organ damage.

Prevention is the smartest strategy. Before prescribing or adding a new drug, clinicians should review the patient’s full medication list, including supplements. If a serotonergic drug is necessary, choosing the lowest effective dose and titrating slowly can lower the danger. For patients already on SSRIs, a wash‑out period is usually required before starting an MAOI—often a two‑week gap. Education matters too; patients should know to alert healthcare providers if they plan to start any new medication, even herbal remedies.

Certain groups need extra attention. People with chronic pain, depression, or migraine often juggle several serotonergic meds, boosting their serotonin syndrome risk, the probability of serotonin toxicity. Polypharmacy in the elderly, liver or kidney impairment that slows drug clearance, and genetic variations in metabolizing enzymes all elevate vulnerability. Regular medication reconciliations and careful dose adjustments can keep these patients safe.

In practice, you’ll find articles that dive deeper into specific drugs and scenarios. For instance, our guide on Paroxetine and PTSD highlights how an SSRI can interact with other serotonergic treatments, while the review on Dexamethasone in pregnancy explains why steroid use rarely adds to serotonin load. By linking these pieces, you’ll see how the broader picture of serotonin syndrome risk shapes safe prescribing and patient counseling. Below you’ll discover a curated collection of posts that break down drug‑specific risks, symptom checklists, and step‑by‑step management plans—giving you actionable insights to protect yourself or your patients from this avoidable medical emergency.

- Colin Hurd

- Oct, 25 2025

- 11 Comments

L‑Tryptophan & Antidepressants: Overlap, Risks & Safe Use

A clear guide on how L‑tryptophan interacts with antidepressants, covering serotonin overlap, safety limits, clinical evidence, and practical dosing tips.