The History of Chloramphenicol: From Discovery to Modern Medicine

- Colin Hurd

- 28 October 2025

- 10 Comments

Chloramphenicol isn’t just another antibiotic. It was the first drug that could fight a wide range of dangerous bacteria - and it saved millions of lives before we even understood how it worked. When it was discovered in 1947, doctors didn’t have many options for treating deadly infections like typhoid fever, plague, and meningitis. Chloramphenicol changed that overnight. It was cheap, effective, and worked where other drugs failed. But its story isn’t just about triumph. It’s also about danger, forgotten risks, and how medicine learned to balance power with caution.

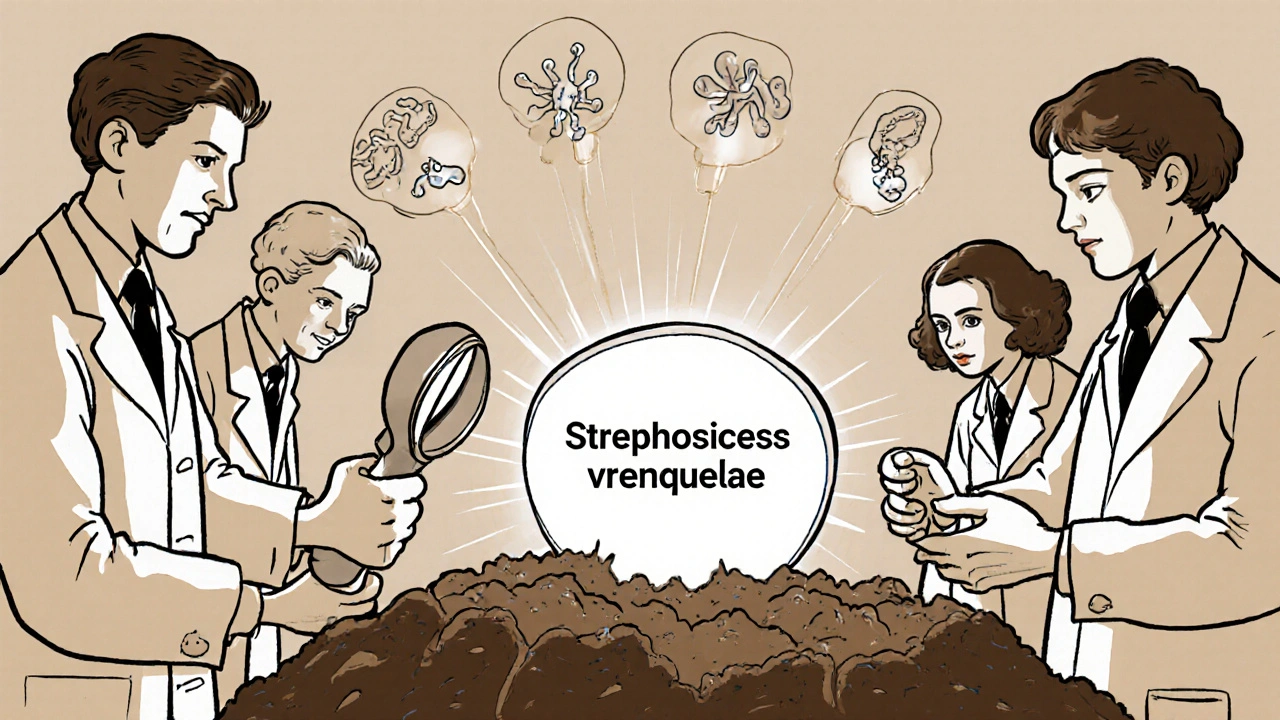

The Discovery That Changed Everything

In 1947, scientists at the pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis were studying soil samples from Venezuela, looking for new antibiotics. One strain of bacteria, Streptomyces venezuelae, caught their attention. It produced a compound that killed a broad range of pathogens - even ones resistant to penicillin. They named it chloramphenicol, after its chemical structure and where it was found.

Before chloramphenicol, typhoid fever killed nearly 20% of those infected. Meningitis in children was almost always fatal. Doctors had few tools. Sulfa drugs helped, but they didn’t work on all bacteria, and resistance was growing fast. Chloramphenicol worked on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria - something no other drug could do at the time. It was the first true broad-spectrum antibiotic.

By 1949, it was being used in hospitals across the U.S. and Europe. In the Korean War, it became the go-to treatment for typhoid among soldiers. In developing countries, where clean water and sanitation were still rare, it was a lifeline. The World Health Organization listed it as an essential medicine by 1977 - a status it still holds today.

How It Works - And Why It’s So Powerful

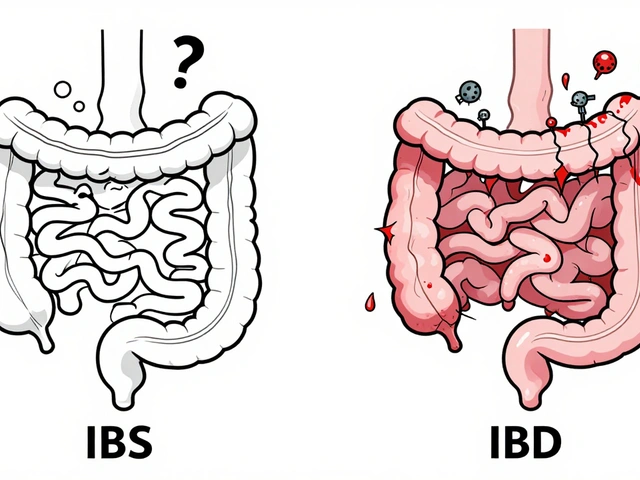

Chloramphenicol stops bacteria from making proteins. It slips into bacterial ribosomes - the tiny machines that build proteins - and jams them. Without proteins, bacteria can’t grow, divide, or survive. Human cells have different ribosomes, so the drug mostly leaves them alone. That’s why it’s so effective: it targets a weakness unique to bacteria.

Unlike many modern antibiotics, chloramphenicol doesn’t rely on the body’s immune system to finish the job. It kills bacteria directly. That’s why it worked so well in people with weakened immunity - like newborns with meningitis or malnourished children in war zones.

It also penetrates tissues easily. It crosses the blood-brain barrier, making it one of the few drugs that could treat meningitis before newer options arrived. It gets into the eyes, the lungs, even the bones. That’s why it was used for serious eye infections, bone infections, and deep abscesses when other drugs failed.

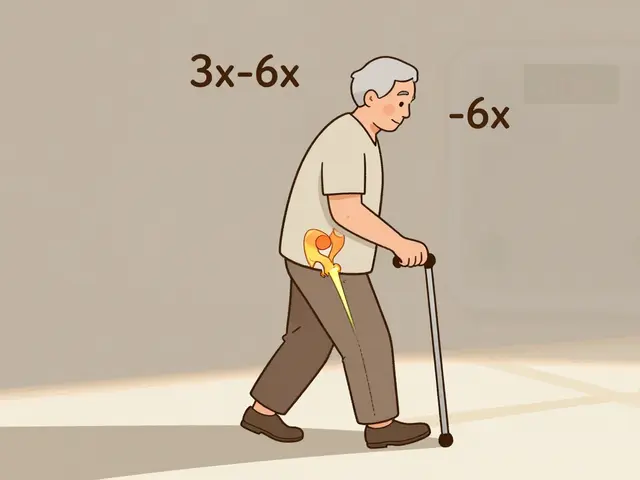

The Dark Side: A Silent Killer

By the early 1950s, doctors noticed something terrifying. A small number of patients - mostly children - started dying suddenly. No fever. No warning. Just bone marrow failure. Their blood counts dropped. They couldn’t make red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Many bled internally or died of infection.

The cause? A rare but deadly side effect called aplastic anemia. It happened in about 1 in 24,000 people who took chloramphenicol. And there was no way to predict who it would hit. The risk wasn’t tied to dose or duration. One person could take it for five days and be fine. Another took the same dose and never woke up.

It wasn’t just aplastic anemia. A more common, reversible problem called bone marrow suppression showed up in up to 1 in 10 patients. Their blood counts dipped, then bounced back after stopping the drug. But aplastic anemia? That was permanent. Often fatal.

By 1952, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had issued a warning. By 1955, it was pulled from the U.S. market for oral use. It stayed available for eye drops and topical use - where the dose was tiny - but systemic use was restricted. Many countries followed suit.

Why It Never Disappeared

Even with the risks, chloramphenicol never vanished. Why? Because in some places, there was nothing else.

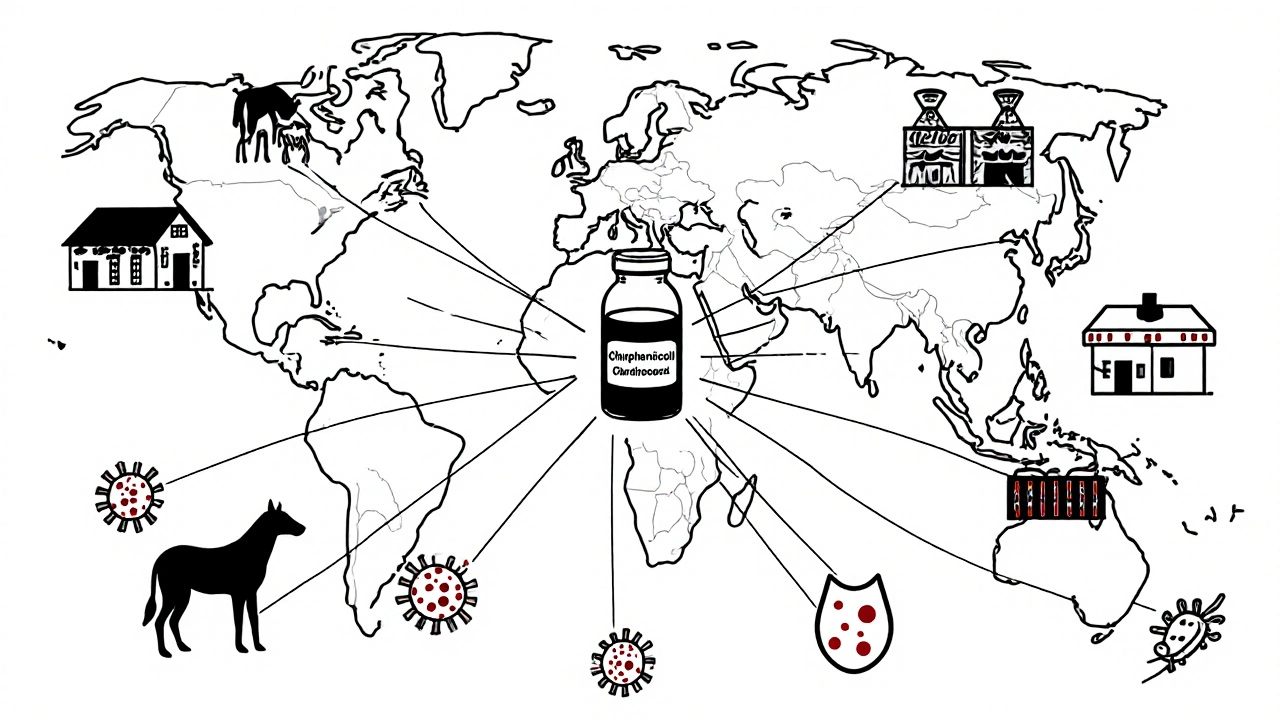

In rural India, Bangladesh, and parts of Africa, typhoid fever still kills thousands every year. Antibiotics like ciprofloxacin and azithromycin are expensive. Chloramphenicol costs less than $1 for a full course. It’s stable without refrigeration. It’s available in tablets, capsules, and even liquid suspensions for children.

For neonatal sepsis in low-resource settings, chloramphenicol remains the first-line treatment. The WHO still recommends it for meningitis in areas where ceftriaxone isn’t available. In outbreaks of plague or tularemia, it’s still a key tool.

Doctors now use it carefully. They avoid it in newborns (who can’t process it well and risk ‘gray baby syndrome’). They monitor blood counts. They use it for short courses - rarely more than 7-10 days. And they never use it for simple infections like sore throats or ear infections.

Modern Use: A Last Resort, But Still Vital

Today, chloramphenicol is rarely used in wealthy countries. It’s been replaced by safer, more targeted antibiotics like fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and macrolides. But in the global health toolkit, it’s still irreplaceable.

In 2020, a study in the Lancet Infectious Diseases found that chloramphenicol was the most effective drug for treating multidrug-resistant typhoid in children in Nepal - better than azithromycin or ceftriaxone. In outbreaks of drug-resistant infections, when everything else fails, chloramphenicol often works.

It’s also used in veterinary medicine. In pets and livestock, it treats serious infections where other drugs are too expensive or unavailable. That’s controversial - because using it in animals can lead to resistance in human pathogens.

Some countries have banned its use in food animals. The European Union and the U.S. FDA restrict it heavily. But in parts of Southeast Asia and Latin America, it’s still used in farming. That’s one reason why resistance is growing. Bacteria are starting to evolve enzymes that break down chloramphenicol before it can kill them.

The Legacy of a Double-Edged Sword

Chloramphenicol taught medicine a brutal lesson: the most powerful drugs are often the most dangerous. Its discovery showed that we could defeat once-deadly infections. Its side effects showed that we had to respect the cost.

It led to better drug safety testing. It pushed regulators to demand long-term monitoring for bone marrow toxicity. It forced doctors to think twice before prescribing a drug - even if it worked perfectly.

Today, chloramphenicol is a relic of a time when antibiotics were miracles - and when we didn’t yet know how to use them safely. But it’s not obsolete. In places where medicine is scarce, it’s still saving lives. In labs, it’s helping scientists understand how bacteria resist drugs. In history books, it’s a reminder that progress isn’t always clean. Sometimes, it comes with a price.

Is chloramphenicol still used today?

Yes, but only in specific cases. It’s still used in low-income countries for typhoid, meningitis, and neonatal sepsis. It’s also used as eye drops for bacterial conjunctivitis and in veterinary medicine. In wealthy countries, it’s a last-resort drug when other antibiotics fail or aren’t available.

Why is chloramphenicol banned in some countries?

It’s not fully banned, but its systemic use (oral or injectable) is heavily restricted because of the risk of aplastic anemia - a rare but often fatal bone marrow disorder. The risk is small, but irreversible. In the U.S., oral chloramphenicol is not approved for general use. Topical forms like eye drops are still allowed because the dose is tiny.

What is gray baby syndrome?

Gray baby syndrome is a life-threatening reaction that can happen in newborns, especially premature babies. Their livers can’t break down chloramphenicol properly, so it builds up in the blood. This causes low blood pressure, gray-blue skin color, breathing problems, and even death. That’s why chloramphenicol is avoided in newborns unless absolutely necessary - and even then, it’s given under strict monitoring.

Can chloramphenicol cause antibiotic resistance?

Yes. Overuse - especially in agriculture and in places where it’s used without prescriptions - has led to resistant strains of bacteria. Some Salmonella and E. coli now carry genes that produce enzymes to break down chloramphenicol. This makes the drug less effective and threatens its future use in serious infections.

How does chloramphenicol compare to modern antibiotics?

Modern antibiotics like ceftriaxone, azithromycin, and ciprofloxacin are safer and more targeted. They have fewer side effects and are easier to monitor. But chloramphenicol still beats them in cost, stability without refrigeration, and effectiveness against multidrug-resistant strains. In resource-poor settings, that makes it the best option - even with its risks.

Comments

Adam Walter

Chloramphenicol is one of those drugs that makes you realize medicine isn’t about perfection-it’s about survival. The fact that it still saves lives in rural India while being banned in the U.S. isn’t hypocrisy-it’s pragmatism. One man’s last resort is another man’s only hope. And let’s be real: if you’re feeding a starving child in Bangladesh with no access to IV antibiotics, you don’t care about a 1-in-24,000 risk. You care about the 1-in-1 chance they’ll die without it.

Modern pharma wants shiny, safe, patentable drugs. But chloramphenicol? It’s a 70-year-old molecule that costs less than a cup of coffee. No corporate board ever got rich off it. That’s why it’s still in the WHO’s essential list. Not because we’re backward, but because we’re honest.

And yes, aplastic anemia is terrifying. But so is watching a baby turn gray because you couldn’t afford ceftriaxone. The real scandal isn’t chloramphenicol-it’s the global health inequality that forces doctors to choose between two horrors.

October 29, 2025 AT 16:32

Allen Jones

EVERYTHING YOU’RE TELLING ME IS A LIE. 😈

Chloramphenicol was NEVER about saving lives-it was a CIA experiment to test how fast populations could be controlled with cheap, toxic drugs. The aplastic anemia? That was the REAL goal. They knew. They always knew. And now they’re using the ‘developing world’ excuse to keep poisoning kids. You think the WHO is innocent? LOL. They’re funded by Big Pharma who want you to forget about penicillin alternatives.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘gray baby syndrome’-that’s just a cover for something way darker. Ask yourself: why did they ban it in the US but still push it abroad? Coincidence? I think NOT.

They’re testing it. On us. On the poor. On the helpless. And you’re just nodding along like a good little sheep. 🐑

October 30, 2025 AT 22:44

jackie cote

Chloramphenicol's legacy is a masterclass in medical ethics. Its continued use in low-resource settings isn't an oversight-it's a moral imperative. The cost-benefit analysis is clear. When alternatives are unattainable, the least harmful option becomes the only responsible one. We must not let privilege blind us to necessity.

November 1, 2025 AT 20:57

ANDREA SCIACCA

OMG YOU GUYS THIS IS SO DEEP LIKE WHO EVEN KNEW?? 😭 Chloramphenicol is basically the anti-hero of antibiotics like it’s the brooding vampire of medicine who saved millions but also kinda ruined a few lives and now everyone’s like ‘we still love you but we’re scared’ 🖤💉 And don’t even get me started on how the U.S. is like ‘we’re too fancy for this’ while the rest of the world is like ‘thank you Jesus for this $1 pill’ #AmericaIsTheProblem #GlobalHealthIsntAClub

November 3, 2025 AT 01:05

Camille Mavibas

i just read this and cried a little 😢 it’s wild how something so simple can be so powerful-and so dangerous. i’m so grateful for the doctors who still use it carefully. and for the people who make sure it’s available where it matters most. we forget that medicine isn’t just about the latest tech. sometimes, it’s about a pill that costs less than a candy bar. thank you for writing this. 🌍💙

November 3, 2025 AT 16:58

Shubham Singh

You people in the West act like chloramphenicol is some ancient relic. But in my village in Bihar, my cousin survived meningitis because of it. No fancy hospitals. No IV drips. Just a bottle of syrup from the local clinic.

And now you want to call it dangerous? What’s dangerous is telling a mother in rural India she can’t save her child because your fancy Western guidelines say so. You don’t get to judge from your air-conditioned offices while kids die because you can’t be bothered to fund real solutions.

This isn’t about science. It’s about power. And you’re the ones holding the leash.

November 4, 2025 AT 13:53

Hollis Hamon

I’ve worked in emergency medicine for over 20 years. I’ve seen chloramphenicol used in three cases-each one a last resort. Each one, a child with no other options.

It’s not glamorous. It’s not profitable. But it works. And when you’re holding a trembling infant with sepsis and the IV line won’t hold, you don’t ask if it’s safe. You ask if it’s possible.

That’s the quiet dignity of this drug. It doesn’t need a marketing campaign. It doesn’t need a patent. It just… helps.

Let’s not romanticize it. Let’s not demonize it. Let’s just make sure it’s available where it’s needed-and that we never forget the people who depend on it.

November 5, 2025 AT 15:23

Gurupriya Dutta

I’m a microbiologist in Delhi. We use chloramphenicol for neonatal sepsis when ceftriaxone isn’t available. We monitor CBCs daily. We limit courses to 7 days. We don’t use it for UTIs or sore throats.

Resistance is growing, yes. But it’s not because we’re careless. It’s because we’re forced to use it-because the system failed. If we had access to affordable, reliable alternatives, we’d switch tomorrow.

The problem isn’t chloramphenicol. The problem is that we’re still treating global health like a charity case instead of a human right.

November 7, 2025 AT 03:47

Michael Lynch

It’s funny how we treat drugs like they’re heroes or villains. Chloramphenicol isn’t either. It’s just a molecule. It does what it does. The real story is us-the humans who decide who gets to live, who gets to die, and who gets to decide what’s ‘safe’.

It’s not about the drug. It’s about who we are when no one’s watching.

And honestly? I’m not sure I like the answer.

November 8, 2025 AT 07:38

Melissa Thompson

I’m sorry, but this article is dangerously naive. The U.S. banned chloramphenicol for a reason: because we have standards. Because we care about patient safety. The fact that other countries are still using it proves they’re backward, not brave. Modern medicine doesn’t need 1940s relics. We have precision antibiotics, genomic testing, and AI-driven diagnostics. To cling to chloramphenicol is to glorify ignorance. If you can’t afford ceftriaxone, the solution isn’t to poison children with outdated toxins-it’s to fix the system. Not to romanticize the suffering.

November 10, 2025 AT 06:25