Fixed-dose combination drugs: what they are and why they exist

- Colin Hurd

- 10 February 2026

- 12 Comments

Have you ever looked at your medicine cabinet and thought, why am I taking four different pills just to manage my blood pressure? You’re not alone. That’s where fixed-dose combination drugs come in - a simple idea with a big impact: two or more medicines in one pill.

These aren’t just convenience packs. A fixed-dose combination drug (FDC) is a single tablet or capsule that contains two or more active ingredients, each in a fixed, unchangeable amount. You can’t take half a pill to reduce one drug while keeping the other at full strength. That’s the whole point - and also the biggest limitation.

Why do FDCs even exist?

It starts with real-life problems. Imagine you have high blood pressure and diabetes. Your doctor prescribes three pills for your BP, two for your sugar, and one for cholesterol. That’s six pills a day. Now add a pill for gout, another for acid reflux. Soon, you’re swallowing a handful of pills every morning. People forget. They get overwhelmed. They stop taking them. And that’s when things go wrong - hospital visits spike, complications grow, costs climb.

FDCs cut through that mess. By combining two or more drugs into one pill, they reduce pill burden. Studies show patients are up to 30% more likely to stick with their treatment when they take fewer pills. That’s not a small win. It’s life-changing for people with chronic conditions like heart disease, HIV, or tuberculosis.

Take HIV treatment. In the early 2000s, patients had to take 10-20 pills a day. Today, many take one pill a day - a single FDC with three antiretrovirals. That single change turned a daily chore into a manageable habit. Survival rates jumped. Transmission rates dropped. This isn’t theory - it’s fact, backed by decades of real-world data from the World Health Organization.

How are FDCs made? Not all combinations are created equal

Just because two drugs are in the same pill doesn’t mean they should be. The WHO has clear rules for when an FDC makes sense:

- The drugs must work in different ways - like one blocking a receptor, another reducing fluid buildup.

- They must have similar how-long-they-last-in-your-body profiles. If one lasts 4 hours and the other lasts 12, you can’t time them right in one pill.

- The combo must not make side effects worse. No point in combining two drugs that both wreck your liver.

Some FDCs are brilliant. Sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim for urinary infections. Rifampicin + isoniazid for tuberculosis. Levodopa + carbidopa for Parkinson’s. These aren’t just convenience - they’re science-backed improvements.

But not all FDCs pass the test. Some are just clever business moves. A company’s big-selling BP drug is about to lose patent protection. So they slap it together with a generic diuretic, file for a new patent, and keep profits rolling. These are called “lifecycle extension” FDCs. Payers - insurance companies, governments - know this trick. And they’re getting smarter about it. They demand proof: Does this combo actually improve outcomes? Or is it just a way to delay generics?

What’s in it for patients? The real benefits

Let’s break it down:

- Less clutter: One pill instead of three. Fewer bottles. Easier to pack for travel.

- Lower cost: One co-pay instead of three. For people on fixed incomes, that adds up fast.

- Better timing: No need to remember “take the red pill with breakfast, the blue one at lunch, the green one at night.” One time, one pill.

- More control: For conditions like hypertension or diabetes, hitting targets early and consistently matters. FDCs help get there.

Real-world data from the U.S. FDA shows that between 2010 and 2015, 63 FDCs were approved out of 656 total new drugs. That’s nearly 10%. And among those, over half used the 505(b)(2) approval path - meaning they built on existing drugs. That’s efficient. But here’s the catch: even with that shortcut, regulators still required full clinical trials for 51% of them. Why? Because they had to prove each ingredient contributed to the benefit. You can’t just glue two drugs together and call it a breakthrough.

The flip side: When FDCs don’t work

Fixed dose means fixed. No flexibility. That’s the trade-off.

What if your blood pressure drops too low on the BP component, but your diabetes needs a higher dose of the sugar-lowering drug? You can’t adjust one without the other. You might have to stop the whole pill - even if one part is helping. That’s dangerous.

Also, not all drugs play nice together. One might speed up how fast the other gets broken down. Or one might cause nausea, and the other makes you dizzy. Together? You feel awful. That’s why the FDA and EMA require detailed studies on how the drugs interact in the body - not just in test tubes, but in real people.

And then there’s the adherence paradox. In some places - like France and Spain - researchers found that FDCs for HIV didn’t improve adherence as expected. Why? Because patients had been on the individual drugs for years. They knew how each one affected them. Switching to a combo made them feel like they lost control. Trust broke down. Sometimes, familiarity beats convenience.

What’s next for FDCs?

The future isn’t just about more pills. It’s about smarter pills.

Researchers are now looking at FDCs for cancer, Alzheimer’s, and autoimmune diseases - conditions where hitting multiple targets at once could change outcomes. One new FDC in trials combines a drug that blocks tumor growth with another that wakes up the immune system. Early results are promising.

But the bar is higher than ever. Regulators aren’t just asking, “Does it work?” They’re asking, “Is it better than taking the drugs separately?” “Does it save lives?” “Does it cut hospital visits?”

And patients? They’re asking, “Can I still adjust my dose if I need to?” “Will this cost me more?” “Is this really helping, or just keeping a company profitable?”

The answer isn’t simple. FDCs are powerful tools - but they’re not magic. They work best when they’re built on solid science, not just business strategy. When they’re tailored to real patient needs. When they’re not just a pill, but a solution.

For millions of people, that’s exactly what they are. One pill. One dose. One less thing to worry about.

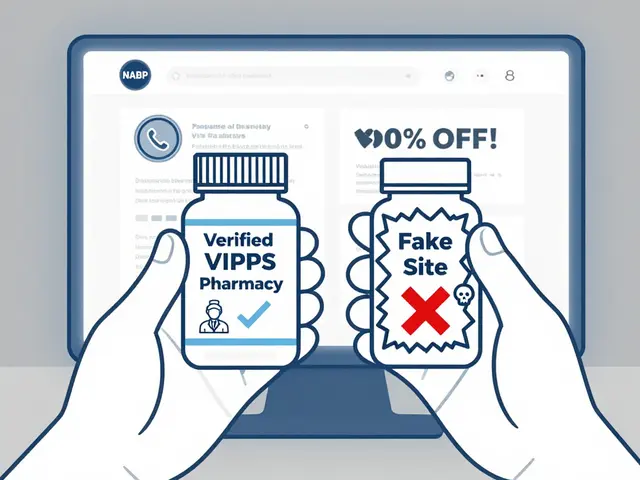

Are fixed-dose combination drugs safe?

Yes - but only if they’re well-designed. Regulators like the FDA and WHO require strong evidence that each drug in the combo contributes to the benefit and doesn’t increase harm. FDCs for HIV, TB, and hypertension have decades of safety data. But poorly thought-out combinations - especially those created just to extend a drug’s patent - can lead to side effects, overdosing, or ineffective treatment. Always ask your doctor: Why this combo? Is there proof it’s better than taking the drugs separately?

Can I split or adjust the dose of a fixed-dose combination drug?

No. Because the ingredients are fixed in one pill, you can’t change the amount of one drug without changing the other. If your doctor needs to adjust one component - say, lower your BP drug but keep your diabetes dose the same - you’ll likely need to switch back to separate pills. Some pharmacies offer custom compounding, but that’s rare and not covered by insurance. Always talk to your prescriber before changing how you take your meds.

Why are FDCs common in blood pressure and diabetes treatment?

Because these conditions often need multiple drugs to control them effectively. High blood pressure, for example, rarely responds to just one pill. Combining a diuretic with an ACE inhibitor or calcium blocker can lower pressure faster and with fewer side effects than using higher doses of a single drug. The same goes for diabetes - combining metformin with a GLP-1 agonist or SGLT2 inhibitor tackles different pathways. These combos aren’t just convenient - they’re clinically superior.

Are generic FDCs as good as brand-name ones?

Yes - if they’re approved by regulators. Generic FDCs must prove they deliver the same amount of each drug into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name version. The FDA requires bioequivalence testing. That means your generic FDC should work just like the original. The big difference? Cost. Generics are often 80-90% cheaper. Many patients switch to generics to save money without losing effectiveness.

Do FDCs increase the risk of drug interactions?

They can - because you’re now taking two active drugs at once. That doubles the chance of interactions with other medications, supplements, or even foods. For example, some FDCs for high blood pressure can interact dangerously with NSAIDs like ibuprofen or potassium supplements. Always tell your pharmacist and doctor about every pill, herb, or supplement you take. They’ll check for hidden risks.

Final thought: One pill, many stories

Fixed-dose combinations aren’t perfect. But they’re real. For the person who forgets to take their pills. For the retiree on a fixed income. For the parent juggling three chronic conditions. For the person in a rural clinic with no pharmacy nearby - one pill can mean the difference between staying healthy and ending up in the hospital.

They’re not magic. But when done right - with science, not just profit - they’re one of the quietest, most powerful tools in modern medicine.

Comments

christian jon

Oh MY GOD. I can't believe people still don't get this. FDCs aren't just 'convenient'-they're a goddamn revolution in chronic care. I had my grandpa on six pills a day. Six. He'd forget, get confused, start skipping them. Then we switched him to three FDCs? Boom. One morning routine. No more 'which pill is which?' panic. His BP stabilized. His kidney numbers improved. And no, it wasn't just placebo-he actually started eating better because he wasn't drowning in a pill mountain. This isn't marketing. This is life-saving design. Stop acting like it's some corporate scam when it's literally keeping people out of the ER.

February 12, 2026 AT 03:07

steve sunio

lol so u mean to tell me u can just glue 2 drugs 2gether and call it science? wtf. i mean like if u have high bp and diabetes why not just take 2 pills? its not that hard. also who even uses these? old people? yeah they forget pills. but maybe they shouldnt be driving or managing their own meds? smh.

February 13, 2026 AT 16:37

Robert Petersen

I love how this post breaks it down so clearly. Seriously, FDCs are one of those quiet wins in medicine that don’t make headlines but change lives. My mom’s been on an FDC for hypertension and diabetes for 3 years now. She says it’s the first time she’s felt like her meds aren’t a full-time job. And yeah, some combos are sketchy-patent extensions, yuck-but the good ones? They’re pure genius. If we can make treatment easier without sacrificing safety, why wouldn’t we? Kudos to the researchers and regulators who actually prioritize patient outcomes over profit.

February 14, 2026 AT 19:09

Craig Staszak

I've been on an FDC for HIV since 2018. One pill. One time. No more counting. No more anxiety. The WHO got this right. It's not about convenience-it's about dignity. When you're not constantly reminded you're sick because you're juggling 15 pills, you start living again. And yes, I know some combos are just corporate tricks. But don't throw the baby out with the bathwater. The science is solid when the science is done right

February 16, 2026 AT 04:33

Jason Pascoe

I work in pharmacy in Sydney and I see this daily. Patients love FDCs. Especially the elderly. One bottle instead of three. Less trips to the pharmacy. Fewer errors. But here’s the thing-sometimes the combo doesn’t fit. Like that one guy who needed his diuretic lowered but his ACE inhibitor kept at full dose? We had to go back to separate pills. FDCs are powerful, but they’re not one-size-fits-all. Always needs a personalized touch. And yeah, generics? Totally fine. Bioequivalence isn’t a myth.

February 16, 2026 AT 10:09

Sonja Stoces

I'm so tired of people acting like FDCs are some miracle cure 🙄 Like, sure, it's easier to take one pill... but what if you're one of the 20% who gets a weird side effect from the combo? I had a friend on a BP+diabetes FDC and she got dizzy + nausea. Couldn't adjust. Had to go back to separate pills. And the cost? Sometimes it's HIGHER than generics. So much for 'cheaper'. This whole thing feels like a marketing ploy wrapped in a lab coat. #NotAllFDCsAreEqual

February 17, 2026 AT 23:08

Annie Joyce

I’ve been a nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen FDCs turn people’s lives around. Especially in underserved communities. Imagine trying to manage five meds when you don’t have a car, can’t read well, and your phone dies every other day. One pill? That’s not convenience-it’s equity. And yes, some combos are sketchy. But the FDA doesn’t just rubber-stamp them. They require clinical data. Real data. Not just ‘looks similar’. If you’re skeptical, look at the HIV data. Mortality dropped. Transmission dropped. That’s not corporate magic. That’s science.

February 18, 2026 AT 10:07

Rob Turner

FDCs are fascinating because they force us to ask: what does 'good medicine' even mean? Is it about precision? Or about humanity? The fact that a single pill can help someone in rural Nigeria take their meds consistently... that’s not chemistry. That’s compassion engineered. And yeah, some companies abuse it. But the solution isn’t to ban FDCs-it’s to demand better regulation. More transparency. Less patent gaming. We can do better. And we will

February 19, 2026 AT 04:00

Luke Trouten

The key insight here is that adherence is not a behavioral issue-it’s a design issue. People aren’t lazy. They’re overwhelmed. The human brain can’t reliably manage six distinct dosing schedules. That’s not a moral failing. That’s cognitive load. FDCs reduce that load. And when you reduce cognitive load, you don’t just improve compliance-you improve outcomes across the board: hospitalizations, mortality, quality of life. This isn’t anecdotal. It’s meta-analytic. The evidence is robust, replicated, and overwhelming. The question isn’t whether FDCs work. It’s why we don’t use them more often.

February 19, 2026 AT 10:58

Gabriella Adams

The regulatory pathway for FDCs under 505(b)(2) is frequently misunderstood. It is not a 'shortcut'-it is a scientifically rigorous framework that leverages existing safety data while requiring new evidence for the combination. The FDA mandates bioequivalence, pharmacokinetic studies, and clinical endpoints for over half of these approvals. To suggest they’re merely repackaged generics is inaccurate. The science is stringent. The bar is high. And the results-reduced hospitalizations, improved survival-are measurable and significant. This is innovation grounded in evidence.

February 19, 2026 AT 18:31

Kristin Jarecki

It is imperative to recognize that fixed-dose combinations represent a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategy, particularly for multi-morbidity management. The clinical evidence supporting their efficacy in hypertension, diabetes, and HIV is not merely correlational-it is causal, longitudinal, and validated across diverse populations. Regulatory agencies require demonstrable superiority or non-inferiority in composite endpoints. The assertion that FDCs are primarily profit-driven is reductive and ignores the substantial body of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating improved health outcomes, reduced polypharmacy-related errors, and enhanced patient-reported quality of life.

February 20, 2026 AT 05:39

Jim Johnson

I used to think FDCs were just for old folks. Then my brother got diagnosed with TB. He was on 4 separate pills. Every. Single. Day. He’d forget. He’d get mad. He’d stop. Then they switched him to a two-drug FDC. He started taking it. He finished his treatment. He’s healthy now. I didn’t know this stuff mattered so much. Thanks for explaining it so well. Sometimes the simplest ideas are the most powerful.

February 21, 2026 AT 18:32