Malignant Hyperthermia and Anesthesia: What You Need to Know About This Life-Threatening Reaction

- Colin Hurd

- 21 January 2026

- 8 Comments

When you walk into a hospital for surgery, you expect safety. You trust the team to keep you stable, to monitor your breathing, your heart, your temperature. But there’s a hidden danger lurking in some anesthetic drugs - one that can turn a routine procedure into a medical emergency in minutes. This is malignant hyperthermia, a rare but deadly reaction triggered by certain anesthesia medications in genetically susceptible people. It doesn’t care if you’re young, fit, or have never had a problem before. It strikes without warning, and if you don’t know the signs, it can kill.

What Exactly Is Malignant Hyperthermia?

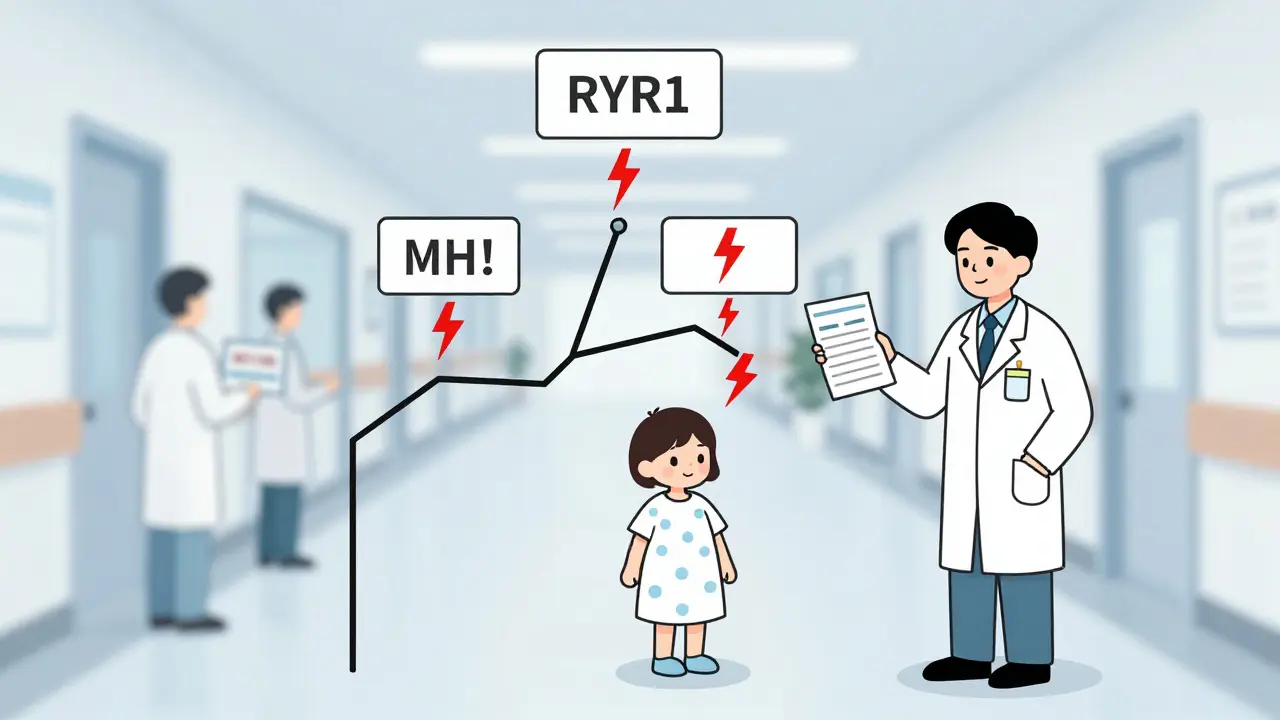

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) isn’t an allergy. It’s not an infection. It’s a genetic flaw in how your muscles handle calcium. In people with MH, a specific mutation - most often in the RYR1 gene on chromosome 19 - causes muscle cells to release too much calcium when exposed to certain anesthetics. This triggers a runaway chain reaction: muscles lock up, your body burns through oxygen like a furnace, and your temperature skyrockets. Without quick action, your organs start shutting down.

The condition was first recognized in Australia in 1960, after four otherwise healthy patients died during routine surgeries. Since then, we’ve learned a lot. About 70% of MH cases are linked to RYR1 mutations. Another 1% involve CACNA1S. But here’s the catch: you can have the mutation and never know it - until you’re under anesthesia.

Which Anesthesia Drugs Trigger MH?

Not all anesthetics are dangerous. The real triggers are specific volatile gases and one muscle relaxant:

- Volatile anesthetics: sevoflurane, desflurane, isoflurane - the gases you breathe during surgery

- Succinylcholine: a fast-acting muscle relaxant often used to help intubate patients

These drugs are common. They’re fast, effective, and used in thousands of surgeries every day. But for someone with MH, even a single breath of sevoflurane can start the crisis. The reaction usually begins within minutes of exposure, though it can sometimes take up to 24 hours. That’s why monitoring doesn’t stop the moment surgery ends.

Safe alternatives exist - like propofol, ketamine, lidocaine, and regional blocks - but they’re not always the first choice. That’s why knowing your risk matters.

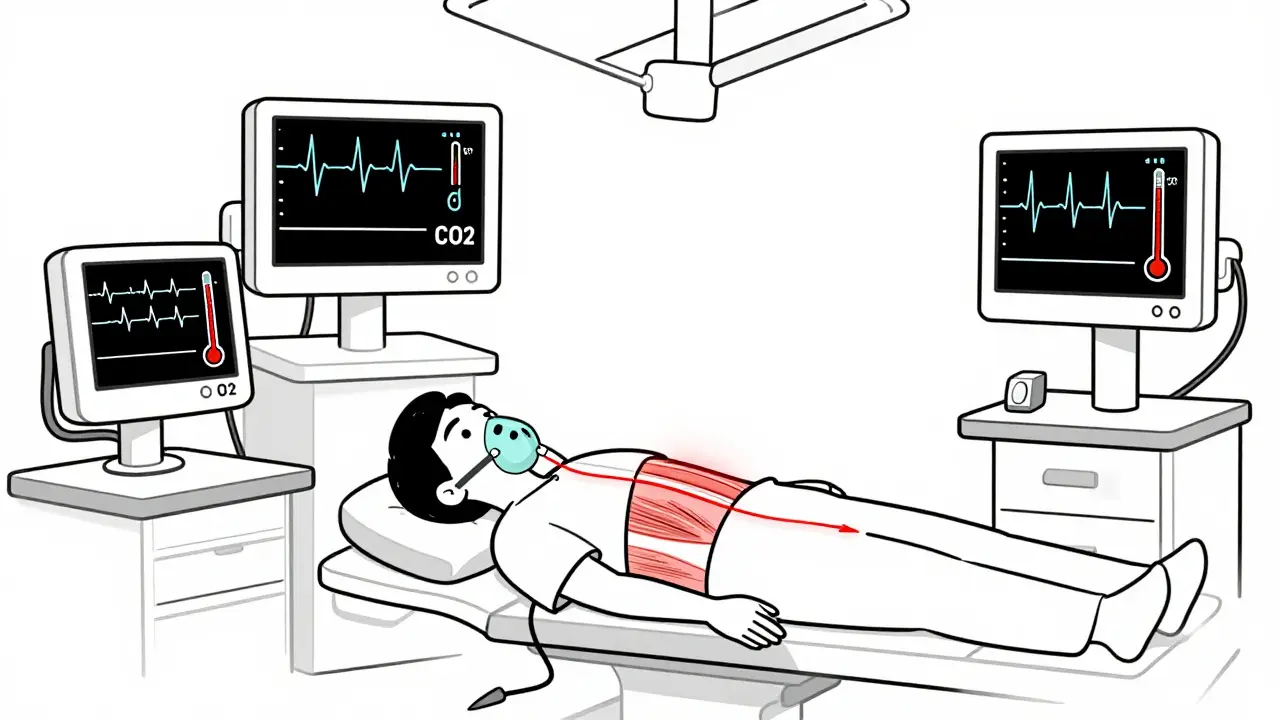

How Do You Know It’s Happening?

Early signs are subtle. They’re easy to miss if you’re not looking for them. The first red flag? A sudden, unexplained spike in heart rate - over 120 beats per minute. Then comes faster breathing, even if you’re on a ventilator. The most telling sign? A rise in carbon dioxide (ETCO2) above 55 mmHg. That’s your body screaming that it’s overheating and burning through oxygen too fast.

Within minutes, you might see:

- Masseter muscle rigidity - a locked jaw that won’t open after intubation

- Body temperature climbing past 104°F (40°C), sometimes hitting 109°F (43°C)

- Dark, tea-colored urine - a sign of muscle breakdown (rhabdomyolysis)

- High potassium levels, acidosis, and unstable blood pressure

One anesthesiologist on Reddit described catching MH in a 28-year-old man when his ETCO2 hit 78 mmHg and his heart rate jumped to 142. He had no family history. No prior issues. Just a routine tonsillectomy. That’s the scary part: 29% of MH cases happen in people with no known risk factors.

What Happens If It’s Not Treated?

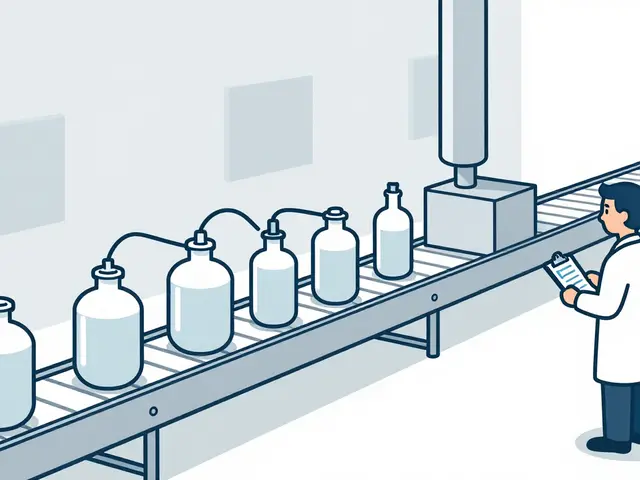

Before 1970, 80% of MH cases were fatal. Patients died from cardiac arrest, organ failure, or uncontrollable bleeding. The turning point? The discovery of dantrolene.

Dantrolene is the only drug that directly stops MH. It works by blocking calcium release in muscle cells. But it’s not easy to use. The old version, Dantrium®, took 22 minutes to mix - time you don’t have. The newer version, Ryanodex®, dissolves in one minute. It’s the standard now. But each vial costs about $4,000. Hospitals are required to keep at least 36 vials on hand - that’s $144,000 worth of emergency medication, just in case.

Without dantrolene, survival chances drop fast. If treatment starts within 20 minutes of symptoms, survival is nearly 100%. Wait 40 minutes? Mortality jumps to 50%. That’s why speed isn’t just important - it’s everything.

How Is MH Treated?

There’s no room for hesitation. The protocol is clear and must be followed exactly:

- Stop all triggering agents immediately. Turn off the gases. Stop succinylcholine.

- Give dantrolene. Start with 2.5 mg/kg IV. Repeat every 5-10 minutes until symptoms fade. Max dose: 10 mg/kg. Some severe cases need 20-30 mg/kg.

- Hyperventilate with 100% oxygen. At least 10 liters per minute. This flushes out CO2 and cools the body.

- Start cooling. Ice packs on neck, armpits, groin. Cold IV fluids. In extreme cases, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be needed.

- Treat complications. Sodium bicarbonate for acidosis. Insulin and glucose for high potassium. Mannitol and furosemide to protect kidneys from muscle breakdown products.

Every minute counts. That’s why top hospitals like Mayo Clinic now keep “MH carts” stocked and ready - within 30 seconds of any operating room. In 2022, they cut treatment delay from 22 minutes to just 4.7 minutes. Survival rates climbed.

Who’s at Risk?

You might think MH only runs in families. But that’s outdated. Yes, it’s inherited - usually autosomal dominant. If a parent has it, you have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation. But 29% of cases occur in people with no family history. Why? Because many families don’t know they carry the gene. Or the mutation is new. Or previous cases were misdiagnosed as “sudden death under anesthesia.”

Children are at higher risk. MH occurs in 1 in 3,000 pediatric surgeries, especially during tonsillectomies. Men are slightly more affected than women. People with certain muscle disorders - like central core disease or multiminicore disease - have a much higher risk.

Even if you’ve had anesthesia before without issues, you’re not safe. MH can develop at any time. The mutation doesn’t care about your age or health history.

What Should You Do If You Suspect MH?

If you’re a patient: Know your family history. If a relative died unexpectedly during anesthesia, tell your doctor. Ask if you should get genetic testing.

If you’re a family member: If someone you love had a bad reaction under anesthesia - especially if they had a stiff jaw, rapid heartbeat, or fever - push for an MH evaluation. The test is called the in vitro contracture test (IVCT), done at specialized labs. The European Malignant Hyperthermia Group updated its criteria in January 2023, lowering the threshold for a positive result. That means more people can be identified.

Genetic testing for RYR1 mutations is available in the U.S. through 27 certified labs. It costs $1,200-$2,500 and detects 95% of known mutations. But it’s not perfect. A negative test doesn’t guarantee safety - only that no known mutation was found.

Why Are So Many Hospitals Unprepared?

Despite decades of awareness, compliance is patchy. In U.S. academic hospitals, 100% follow MHAUS guidelines. In rural centers? Only 63%. Many don’t stock enough dantrolene. Some don’t train staff annually. Some don’t even have a written MH protocol.

That’s why the FDA mandated in 2021 that every facility performing general anesthesia must have an MH emergency kit. That affects over 15,000 locations. But enforcement is inconsistent. In 2022, 22% of rural hospitals reported running out of dantrolene. Ryanodex® has a shelf life of only 21 months. Expired stock can’t be used.

The solution? Training. The American Society of Anesthesiologists requires annual MH simulation drills. Studies show residents need at least three simulations to recognize MH reliably. But many hospitals skip it. And patients? 68% of survivors had never heard of MH before their own crisis.

What’s Next for MH?

The future is promising. In 2023, the FDA approved intranasal dantrolene for pre-hospital use - expected to hit the market in mid-2024. Imagine paramedics or ER staff giving it before the patient even reaches the OR.

Researchers are testing new drugs like S107, which stabilizes the RYR1 channel. And in the long term, CRISPR gene editing could one day correct the mutation. Phase I trials are expected by 2027.

Already, anesthesia machines are getting smarter. Epic Systems rolled out an AI alert in 2024 that flags MH when three signs appear together: rising CO2, fast heart rate, and high temperature. It doesn’t replace human judgment - it supports it.

Final Thoughts

Malignant hyperthermia is rare. But it’s real. And it’s deadly if ignored. The good news? We know how to save people. We have the drugs. We have the protocols. We have the data. What’s missing is awareness - from patients, from families, from hospitals that still don’t take it seriously.

If you’re scheduled for surgery, ask: Do you have dantrolene on site? Is your team trained for MH? If you’ve had a relative die unexpectedly under anesthesia, get tested. Don’t wait for a tragedy to learn the warning signs.

The next time someone goes under anesthesia, they deserve more than luck. They deserve preparation. And now, we have the tools to make sure they get it.

Can malignant hyperthermia happen to anyone?

Yes. While MH is genetic and runs in families, about 29% of cases occur in people with no known family history. You can have the mutation and never know it - until you’re under anesthesia. Even if you’ve had surgery before without issues, you’re not guaranteed to be safe.

What are the most common triggers for malignant hyperthermia?

The main triggers are volatile anesthetic gases - sevoflurane, desflurane, and isoflurane - and the muscle relaxant succinylcholine. These are commonly used in general anesthesia. Safe alternatives like propofol, ketamine, and regional blocks are available and should be used if you’re at risk.

Is there a test to find out if I’m at risk?

Yes. Two main tests exist: genetic testing for RYR1 or CACNA1S mutations, and the in vitro contracture test (IVCT), which measures muscle response to triggering agents. Genetic testing is less invasive and detects 95% of known mutations. IVCT is the gold standard but requires a muscle biopsy and is only done at specialized centers.

How quickly does dantrolene need to be given?

Within 20 minutes of symptom onset. Survival rates drop sharply after 40 minutes. That’s why hospitals must keep dantrolene immediately accessible. The newer Ryanodex® formulation can be mixed in under a minute - a huge improvement over the old Dantrium®, which took 22 minutes.

Can I still have surgery if I have malignant hyperthermia?

Yes - but not with triggering agents. If you’re diagnosed with MH, your anesthesiologist will use a completely safe anesthesia plan: non-triggering drugs like propofol, regional blocks, or local anesthesia. With proper planning, people with MH can safely undergo any surgery. The key is communication and preparation.

What should I do if I suspect someone is having an MH reaction?

Call for help immediately. Demand dantrolene. Stop all volatile anesthetics and succinylcholine. Begin hyperventilation with 100% oxygen. Start active cooling. Call the MHAUS Hotline at 1-800-644-9737 - they provide 24/7 expert guidance. Every second counts.

Comments

dana torgersen

So… like… if you’ve never had anesthesia before, how do you even KNOW you’re at risk?? It’s not like you can just get tested for this unless someone in your family died mysteriously during surgery?? I mean, I had my tonsils out at 7, and I’m fine, but what if I’m one of those 29%?? This is terrifying. I’m going to Google ‘RYR1 genetic test’ right now. I need answers. Now. Please.

January 22, 2026 AT 05:21

Dawson Taylor

The biological mechanism described is both elegant and horrifying. The calcium dysregulation in skeletal muscle, triggered by halogenated anesthetics, represents a profound failure of homeostatic control. The fact that this mutation persists in the population suggests a possible heterozygous advantage, though none has yet been identified. Dantrolene’s mechanism-direct inhibition of ryanodine receptor calcium release-is a triumph of targeted pharmacology. Yet, the economic and logistical barriers to its universal availability remain ethically indefensible.

January 22, 2026 AT 05:37

Janet King

If you are scheduled for surgery, ask your anesthesiologist if they have dantrolene available. Ask if they have trained for malignant hyperthermia emergencies. Ask if they know the protocol. These are simple questions. They should be asked. Always.

January 23, 2026 AT 13:24

Sallie Jane Barnes

Hey everyone-just wanted to say this post saved my life. My brother had a near-miss during a wisdom tooth extraction last year. They didn’t have dantrolene on hand. He was rushed to a bigger hospital. He’s okay now. But I didn’t know ANY of this until I read this. I’m telling every single person I know who’s having surgery. Don’t wait for a crisis. Ask the questions. Be loud. Be annoying. It’s worth it.

January 23, 2026 AT 21:27

Susannah Green

I work in OR nursing. We keep our MH cart stocked, checked weekly, and rehearsed monthly. But I’ve seen hospitals skip training because ‘it’s rare.’ Rare doesn’t mean ‘not going to happen to someone you love.’ One time, a 19-year-old athlete had a jaw lock during intubation. We didn’t know he had a cousin who died under anesthesia. We started dantrolene. He lived. He’s now a firefighter. Don’t underestimate the power of preparation. It’s not just protocol-it’s humanity.

January 25, 2026 AT 16:46

Anna Pryde-Smith

THIS IS A SCAM. They’re making you paranoid so you’ll pay for genetic testing and emergency drugs that cost $144,000 per hospital. Who benefits? Pharma. The hospitals. The ‘MH experts.’ Meanwhile, millions die from preventable infections, medication errors, and delayed care-none of which get this much attention. You’re being manipulated. Stop buying into fear porn. If your surgery is routine, you’re fine. Trust your doctor. Not some Reddit post with a fancy chart.

January 26, 2026 AT 16:35

Vanessa Barber

Maybe MH isn’t the real problem. Maybe the real problem is that we’re still using volatile anesthetics at all. We’ve had propofol for decades. Why not make it the default? Why do we keep clinging to outdated, dangerous tools just because they’re cheaper and faster? The answer is inertia. And profit. And tradition. Not science.

January 27, 2026 AT 14:34

Stacy Thomes

MY BROTHER DIED IN 2012 DURING A TONSILLECTOMY. NO ONE TOLD US ABOUT MH. NO ONE ASKED ABOUT FAMILY HISTORY. WE THOUGHT IT WAS A ‘COMPLICATION.’ THEY DIDN’T EVEN HAVE DANTRYLENE. I SPENT YEARS BEING ANGRY. NOW I SPEND MY TIME TELLING EVERYONE I MEET. IF YOU’RE HAVING SURGERY-ASK. ASK. ASK. DON’T LET MY BROTHER’S DEATH BE IN VAIN.

January 27, 2026 AT 21:39